Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

World Psychology: Psychology by Country · Psychology of Displaced Persons

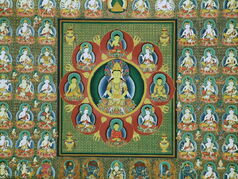

A mandala used in Vajrayana Buddhist practices.

Vajrayāna Buddhism (Also known as Tantric Buddhism, Tantrayana, Mantrayana, Esoteric Buddhism, Diamond Vehicle, ', or 金剛乘 Jingangcheng in Chinese) is an extension of Mahayana Buddhism consisting of differences in the adoption of additional techniques (upaya, or 'skillful means') rather than in philosophy. Some of these upaya are esoteric practices which must be initiated and transmitted only through a skilled spiritual teacher.[1] The Vajrayana is often viewed as the third major 'vehicle' (Yana) of Buddhism, alongside the Theravada and Mahayana.

Subschools[]

Vajrayana exists today in the form of two major sub-schools:

- Tibetan Buddhism, found in Tibet, Bhutan, northern India, Nepal, southwestern and northern China, Mongolia and various constituent republics of Russia that are adjacent to the area, such as: Amur Oblast, Buryatia, Chita Oblast, Tuva Republic, and Khabarovsk Krai. There is also Kalmykia, another constituent republic of Russia that is the only Buddhist region in Europe, located in the north Caucasus. While Vajrayana Buddhism is a part of Tibetan Buddhism (in that it forms a core part of every major Tibetan Buddhist school), it is not identical with it, as the Vajrayana is seen as additional part to the general Mahayana teachings for somewhat advanced students. Vajrayana in Tibetan Buddhism, properly speaking, refers to tantra, Dzogchen (mahasandhi), and Chagchen (mahamudra).

- Shingon Buddhism, found in Japan, includes many esoteric practices which are similar in concept to those used in Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism. However, the lineage for Shingon Buddhism is entirely different than that found in Tibetan Vajrayana, and thus the actual practices are not related. Shingon uses a different set of esoteric scriptures, of primary importance the Mahavairocana Sutra, and a different set of mantras. The founder of Shingon Buddhism is Kukai a Japanese monk who studied in China during the Tang Dynasty, and brought back Vajrayana scriptures, techniques and mandalas that were popular at the time. This lineage of Buddhism died out in China, but was preserved and later flourished in Japan.

Etymology[]

The term "vajra" originally refers to the thunderbolt of Indra, a weapon that was made from an indestructible substance, and which could therefore pierce any obstacle. As a secondary meaning, "vajra" therefore also refers to this indestructible substance, and so is sometimes translated as "adamantine" or "diamond". So the vajrayana is sometimes called "The Adamantine Vehicle" or "The Diamond Vehicle".

A vajra is also a ritual object this is like a small sceptre. It usually takes the form of a bronze rod, like a mace; it has a sphere at its centre, and some number of spokes (most commonly four) at either end, enfolding either end of the rod. The vajra is used in tantric rituals in combination with the traditional bell; symbolically, the vajra represents method and the bell stands for wisdom.

Distinguishing features of Vajrayana[]

Vajrayana Buddhism claims to provide an accelerated path to enlightenment. This is achieved through use of tantra techniques, which are practical aids to spiritual development, and esoteric transmission (explained below). Whereas earlier schools might provide ways to achieve nirvana over the course of many lifetimes, Vajrayana techniques are said to make full enlightenment or buddhahood possible in a shorter time, perhaps in a single lifetime. Vajrayana Buddhists do not claim that Theravada or Mahayana practices are invalid; in fact, the teachings from those traditions are said to lay an essential foundational practice on which the Vajrayana practices may be built. While the Mahayana and Theravada paths are said to be paths to enlightenment in their own right, the teachings from each of those vehicles must be heeded for the Vajrayana to work. It should also be noted that the goal of the Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions is to become a Buddha by following the bodhisattva path, whereas an alternative, and more common, goal for Theravada practice is 'simply' liberation from the cycle of rebirth (samsara) by achieving nirvana. In fact the distinction between these traditions is not always rigid: the tantra sections of editions of the Kangyur sometimes include material not usually thought of as tantric outside the Tibetan tradition, such as the Heart Sutra[2] and even versions of material found in the Pali Canon.[3]

Tantra techniques[]

- Main article: Tantra techniques (Vajrayana)

Tantra Techniques

In Vajrayana there are key times when the mind is more susceptible to be opened. These times are during sex and at the time of death. In Mahayana Buddhism it is possible to attain enlightenment in a single life time by practicing these techniques. One tool used is Deity Tantra.

- Guru Tantra- is a practice where the practitioner focuses on their guru as deity during meditation.

- Deity Tantra- is a fundamental practice in Tantra. In Deity Tantra the meditator visualizes themselves as the deity. The purpose of Deity Tantra is to bring the meditator to the realization that the deity and the self are the same. It allows the meditator to release themselves from worldly attachments. Mandalas are often used as meditation aids in Deity Tantric practice.

The Importance of Mandalas in Deity Tantra- Mandala’s are artwork that represent the deity and the deity’s palace. In the book, The World of Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai Lama describes them as follows. “This is the celestial mansion, the pure residence of the deity.”

- There are several types of Mandalas but the primary ones are

- .the mandala of concentration

- .the cloth painted mandala

- .the mandala of colored sand (primary mandala in tantric practice)

- .the 3D mandala model (usually made in wood or copper)

- .the body mandala of the guru (in Highest Yoga Tantra)

- Deity Tantra is often practiced at the moment directly prior to sexual climax. The practitioner takes a consort and this is practiced in pairs. Often times the couple pictures themselves as the deities in the mandala making love.

Guru and Deity tantra help in the realization and feelings of interconnectedness. Death Tantra- In western culture Death Tantra is a less explored aspect of Tantra techniques. At the time of death the mind is in such a state that opens the mind to enlightenment. Although it is called Death Tantra the practice actually begins in life. It is the accumulation of meditative practice that helps to prepare the practitioner for what they need to do at the time of death. Meditation on death is a common practice with in Buddhist sects. In the book, “The Blooming of a Lotus” there is a meditative practice that concentrates on the impermance of death. The following is an excerpt from that meditative mantra: “Seeing the dead body of my beloved, I breathe in Smiling to the dead body of my beloved I breathe out” Thich Naht Hahn goes onto to say “When we can envision the death of one we love we are able to let go.” Other types of Death Tantra are where the practitioner meditates on their own death. Such meditation prepares practitioners for the time spent between death and rebirth.

- The World of Tibetan Buddhism, His Holiness The Fourteenth Dalai Lama, pg107,Wisdom Publications 1995

The Blooming of a Lotus, Thich Naht Hahn, pgs 56-58, Beacon Press The Blooming of a Lotus, Thich Naht Hahn, pgs 56-58, Beacon Press

Levels of tantra[]

The Sarma or New Translation schools of Tibetan Buddhism (Gelug, Sakya, and Kagyu) divide the Tantras into four hierarchical categories, namely,

- Kriyayoga

- Charyayoga

- Yogatantra

- Anuttarayogatantra

- further divided into "mother", "father" and "non-dual" tantras.

A different division is used by the Nyingma or Ancient school:

- Three Outer Tantras:

- Kriyayoga

- Charyayoga

- Yogatantra

- Three Inner Tantras, which correspond to the Anuttarayogatantra:

- Mahayoga

- Anuyoga

- Atiyoga (Tib. Dzogchen)

- The practice of Atiyoga is further divided into three classes: Mental SemDe, Spatial LongDe, and Esoteric Instructional MenNgagDe.

Esoteric transmission (initiation) and samaya (vow)[]

Main articles: Esoteric transmission, samaya

The other conspicuous aspect of Vajrayana Buddhism is that it is esoteric. In this context esoteric means that the transmission of certain accelerating factors only occurs directly from teacher to student during an initiation and cannot be simply learned from a book. Many techniques are also commonly said to be secret, but some Vajrayana teachers have responded that secrecy itself is not important and only a side-effect of the reality that the techniques have no validity outside the teacher-student lineage.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

If these techniques are not practiced properly, practitioners may harm themselves physically and mentally. In order to avoid these dangers, the practice is kept "secret" outside the teacher/student relationship. Secrecy and the commitment of the student to the vajra guru are aspects of the samaya (Tib. damtsig), or "sacred bond", that protects both the practitioner and the integrity of the teachings.[4]

The esoteric transmission framework can take varying forms. The Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism uses a method called Dzogchen. The Tibetan Kagyu school and the Shingon school in Japan use an alternative method called Mahamudra.

Relationship with Mahayana[]

While tantra and esoterism distinguish Vajrayana Buddhism, it is, from the Tibetan Buddhist point of view, nonetheless primarily a form of Mahayana Buddhism. Sutras important to Mahayana are generally important to Vajrayana, although Vajrayana adds some of its own (see Buddhist texts, List of sutras, Tibetan Buddhist canon). The importance of bodhisattvas and a pantheon of deities in Mahayana carries over to Vajrayana, as well as the perspective that Buddhism and Buddhist spiritual practice are not intended just for ordained monks, but for the laity too.

The Japanese Vajrayana teacher Kūkai expressed a view contrary to this by making a clear distinction between Mahayana and Vajrayana. Kūkai characterises the Mahayana in its entirety as exoteric, and therefore provisional. From this point of view the esoteric Vajrayana is the only Buddhist teaching which is not a compromise with the limited nature of the audience to which it is directed, since the teachings are said to be the Dharmakaya (the principle of enlightenment) in the form of Mahavairocana, engaging in a monologue with himself. From this view the Hinayana and Mahayana are provisional and compromised aspects of the Vajrayana - rather than seeing the Vajrayana as primarily a form of Mahayana Buddhism.

Some aspects of Vajrayana have also filtered back into Mahayana. In particular, the Vajrayana fondness for powerful symbols may be found in weakened form in Mahayana temples where protector deities may be found glaring down at visitors.

The Vajrayana has a rich array of vows of conduct and behaviour which is based on the rules of the Pratimoksha and the Bodhisattva code of discipline. The Ornament for the Essence of Manjushrikirti states:

- Distance yourself from Vajra Masters who are not keeping the three vows[5]

- who keep on with a root downfall, who are miserly with the Dharma,

- and who engage in actions that should be forsaken.

- Those who worship them go to hell and so on as a result.[6]

This as well as other sources express the need to build the Vajrayana on the foundation of the Pratimoksha and Bodhisattva vows. Lay persons can follow the lay ordination. The Ngagpa Yogis from the Nyingma school keep a special lay ordination.

History of Vajrayana[]

India[]

There are differing views as to where Vajrayana began. Some believe it originated in Bengal,[7] now divided between the Republic of India and Bangladesh, with others claiming it began in Udyana, the modern day Swat Valley in Pakistan, or in South India. In the Tibetan tradition, it is claimed that the historical Shakyamuni Buddha taught tantra, but as these are 'secret' teachings outside the teacher/disciple relationship, they were written down generally long after the Buddha's other teachings, known as sutras.

The earliest texts appeared around the early 4th century. Nalanda University in northern India became a center for the development of Vajrayana theory, although it is likely that the university followed, rather than led, the early Tantric movement. India would continue as the source of leading-edge Vajrayana practices up through the 11th century.

(Vajrayana) Buddhism had mostly died out in India by the 13th century, its practices merging with Hinduism, and both tantric religions were experiencing pressure from invading Islamic armies. By that time, the vast majority of the practices were also made available in Tibet, where they were preserved until recently, although the Tibetan version of tantra differs from the original Indian form in many respects.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

In the second half of the 20th century a sizable number of Tibetan exiles fled the oppressive, anti-religious rule of the Communist Chinese to establish Tibetan Buddhist communities in northern India, particularly around Dharamsala. They remain the primary practitioners of Tantric Buddhism in India and the entire world.

China[]

Vajrayana followed the same route into northern China as Buddhism itself, arriving from India via the Silk Road some time during the first half of the 7th century. It arrived just as Buddhism was reaching its zenith in China, receiving sanction from the emperors of the Tang Dynasty. The Tang capital at Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an) became an important center for Buddhist studies, and Vajrayana ideas no doubt received great attention as pilgrim monks returned from India with the latest texts and methods (see Buddhism in China, Journey to the West).

Tibet and other Himalayan kingdoms[]

A Buddhist ceremony in Ladakh.

In 747 the Indian master Padmasambhava traveled from Afghanistan to bring Vajrayana Buddhism to Tibet and Bhutan, at the request of the king of Tibet. This was the original transmission which anchors the lineage of the Nyingma school. During the 11th century and early 12th century a second important transmission occurred with the lineages of Atisa, Marpa and Brogmi, giving rise to the other schools of Tibetan Buddhism, namely Kadampa, Kagyupa, Sakyapa, and Gelukpa (the school of the Dalai Lama).

Japan[]

In 804, Emperor Kammu sent the intrepid monk Kūkai to the Tang Dynasty capital at Chang'an (present-day Xi'an) to retrieve the latest Buddhist knowledge. Kūkai absorbed the Vajrayana thinking and synthesized a version which he took back with him to Japan, where he founded the Shingon school of Buddhism, a school which continues to this day.

Indonesia and Malaysia[]

In the late 8th century, Indian models of Vajrayana traveled directly to the Indonesian island of Java where a huge temple complex at Borobudur was soon built. The empire of Srivijaya was a centre of Vajrayana learning and Atisha studied there under Serlingpa, an eminent Buddhist scholar and a prince of the Srivijayan ruling house. Vajrayana Buddhism survived in Indonesia and Malaysia until eclipsed by Islam in the 13th century.

Mongolia[]

In the 13th century, long after the original wave of Vajrayana Buddhism had died out in China itself, two eminent Tibetan Sakyapa teachers, Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyaltsen and Chogyal Phagpa, visited the Mongolian royal court. Marco Polo was serving the royal court at about the same time. In a competition between Christians, Muslims, and Buddhists held before the royal court, Prince Godan found Tibetan Buddhism to be the most satisfactory and adopted it as his personal religion, although not requiring it of his subjects. As Kublai Khan had just conquered China (establishing the Yuan Dynasty), his adoption of Vajrayana led to the renewal of Tantric practices in China as the ruling class found it useful to emulate their leader.

Vajrayana would decline in China and Mongolia with the fall of the Yuan Dynasty, to be replaced by resurgent Daoism, Confucianism, and Pure Land Buddhism. However, Mongolia would see yet another revival of Vajrayana in the 17th century, with the establishment of ties between the Dalai Lama in Tibet and the remnants of the Mongol Empire. This revived the historic pattern of the spiritual leaders of Tibet acting as priests to the rulers of the Mongol empire. Tibetan Buddhism is still practiced as a folk religion in Mongolia today despite more than 65 years of state-sponsored communism.

Literature on Vajrayana Ethics[]

- Tantric Ethics: An Explanation of the Precepts for Buddhist Vajrayana Practice by Tson-Kha-Pa, ISBN 0-86171-290-0

- Perfect Conduct: Ascertaining the Three Vows by Ngari Panchen, Dudjom Rinpoche, ISBN 0-86171-083-5

- Buddhist Ethics (Treasury of Knowledge) by Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye, ISBN 1-55939-191-X

See also[]

- Dzogchen

- Mahamudra

- Tibetan Buddhist teachers

Notes and references[]

- ↑ [Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World: The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet. Shambhala Publications, Boston: 2001]

- ↑ Conze, The Prajnaparamita Literature

- ↑ Peter Skilling, Mahasutras, volume I, 1994, Pali Text Society[1], Lancaster, page xxiv

- ↑ [Ray, Reginald A. Secret of the Vajra World: The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet. Shambhala Publications, Boston: 2001]

- ↑ this refers to the Pratimoksha, Bodhisattva and Vajrayana vows

- ↑ Tantric Ethics: An Explanation of the Precepts for Buddhist Vajrayana Practice by Tsongkhapa, ISBN 0-86171-290-0, page 46

- ↑ Banerjee, S. C. Tantra in Bengal: A Study in Its Origin, Development and Influence. Manohar. ISBN 8185425639.

External links[]

- The Website of The Office of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.

- The Website of Patrul Rinpoche.

- Dudjom Tersar lineage of Nyingma.

- The Kordong tradition.

- E-Sangha Tibetan Buddhism Forum

- Kagyu lineage. Official website, with biography of Kalu Rinpoche (the 2nd Kalu Rinpoche).

- The Berzin archive. Archive on texts and teachings of Vajrayana, Tibetan Buddhism, Islam and Bon

- Official website of Diamond Way (Ole Nydal).

- Official Sakya lineage website.

- Dilgo Khyentse Fellowship - Shechen.

- Dzongsar Khyentse's website.

- Sakya Dechen Ling.

- Resource page of Sakya lineage.

- Palyul lineage of Nyingma.

- Khyentse Foundation.

- Yongey Foundation.

- Mindrolling lineage of Nyingma.

- Drukpa Kagyu lineage.

- Drikung Kagyu lineage.

- Foundation of the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (Gelug, Lama Zopa).

- Ritual Implements in Tibetan Buddhism: A Symbolic Appraisal.

- Enlightenment: Buddhism Vis-à-Vis Hinduism.

- History of Tibetan Buddhism and the Vajrayana in Tibet (a Karma Kagyu web site.

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |