Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Clinical: Approaches · Group therapy · Techniques · Types of problem · Areas of specialism · Taxonomies · Therapeutic issues · Modes of delivery · Model translation project · Personal experiences ·

|

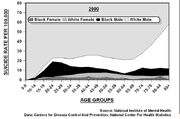

U.S. Suicide Rates by Age, Gender, and Racial Group.

In the United States, males are four times more likely to die by suicide than females. Male suicide rates are higher than females in all age groups (the ratio varies from 3:1 to 10:1). In other western countries, males are also much more likely to die by suicide than females (usually by a factor of 3–4:1). It was the 8th leading cause of death for males, and 19th leading cause of death for females.[1]

Excess male mortality from suicide is also evident from data from non-Western countries. In 1979-81, out of 74 countries with a non-zero suicide rate, two reported equal rates for the sexes (Seychelles and Kenya), three reported female rates exceeding male rates (Papua-New Guinea, Macao, and French Guiana), while the remaining 69 countries had male suicide rates greater than female suicide rates. [2]

Male suicide[]

Suicide and young men[]

The World Health Organization noted a significant increase in young male suicide in the West in the later half of the 20th century (Cantor 2000).

Evidence by country[]

In the Uk the rate rose from 9 per 100,000 in 1974 to 16 per 100,000 in 2000 amongst t25-24 year olds (Office of National statistics, 2005) and remianed the most common cause of death in men under 35 (Department of Health, 20002)

Causes of young male suicide are multifactorial (Hawton, 2000) and are exacerbated by their reluctance to seek help (Griffiths,1992:Addis & Mahalik 2003). Biddle et al 2004, in a study of 3000 16-24 year olds found that the young men were less likely to seek profession help for mental health and suicide issues or to confide in family and friends.

They are often not registered with local healthcare facilities so, for example, in an audit of young male suicides in the London Borough of Camden between 1999 and 2003 showed that only 20% were known to their GPs (Hahne, 2004)

If they are registered they often do not make appointments, if they do they often do not attend or present on the basis of physical rather than psychological symptoms (Royal College of Psychiatrists,1998:McQeen & Henwood, 2002). Then even if healthworkers assess suicide risk young men do not necessarily take up the help that is offered (Jenkins 1997.

Female suicide[]

While there are more completed male suicides than female, females are more likely to attempt suicide. One possible explanation of this statistical phenomenon, supported by a study by Rich, Ricketts, Fowler, and Young, is that males tend to use more "violent, immediately lethal methods of suicide" than females.[3] Another explanation is that females are more likely to use self-harm as a cry for help or an extreme grab for attention, while suicidal males would be more likely to genuinely want to end their lives[How to reference and link to summary or text].

References[]

Addis, ME & Mahalik, J.R. (2003). Men, masculinity and the contexts of health seeking. American Psychologist, 58(1), 5-14.

- Biddle, L., Gunnel, D., Sharp D. & Donovan, J.L. (2004). Factors influencing help seeking in mentally distressed adults: A cross sectional study. British Journal of General Practice, 54(501), 248-253.

Cantor C. (2000) Suicide in the western world In Hawton, K, & Heringen (eds) The International Handbook Of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Chichester. Wiley.

- Hahne, S. (2004) Suicide in Camden: Information for planning a local suicide prevention strategy. Submission for the Part II Examination for Membership of the Faculty of Public Health.

- Halperin, J., Leibowitz, J., Crocker, L., Gsodl, M., Cambell, J., Parrett, N. and Underhill, J.(2008) Clinical Psychology Forum, 191, 25-29.

- Hawton, K. (2000) Sex and suicide:Gender differences in suicidal behaviour. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177,484-485.

- Hawton, K, & Heringen (eds) (2000) The international Handbook Of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Chichester. Wiley.

- Griffiths, S. (1992). The neglected male. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 48,627-629.

- Jenkins, R., Lewis, G., Bebbington, P.,Brugha, T., Farrell, M., Gill, B., et al (1997) The national psychiatric morbidity surveys of Great britain:Initial findings from the household survey. Psychological Medicine, 27, 775-789.

Office of National Statistics (2005). Death rates from suiide by gender and age 1974-2000. Social Trends, 32.]

- ↑ (2001). Teen Suicide Statistics. Adolescent Teenage Suicide Prevention. FamilyFirstAid.org. URL accessed on 2006-04-11.

- ↑ Lester, Patterns, Table 3.3, pp. 31-33

- ↑ Rich, CL, JE Ricketts, RC Fowler and D Young (1988). Some differences between men and women who commit suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry 145: 718–722. PMID 3369559.