Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Cognitive Psychology: Attention · Decision making · Learning · Judgement · Memory · Motivation · Perception · Reasoning · Thinking - Cognitive processes Cognition - Outline Index

Parallax (Greek: παραλλαγή (parallagé) = alteration) is the change of angular position of two stationary points relative to each other as seen by an observer, due to the motion of an observer. Simply put, it is the apparent shift of an object against a background due to a change in observer position.

Introduction[]

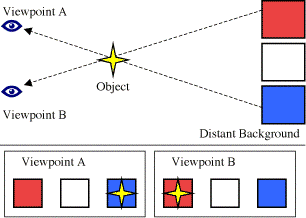

Figure 1: A simplified example of parallax.

Parallax is often thought of as the "apparent motion" of an object against a distant background because of a perspective shift, as seen in Figure 1. When viewed from Viewpoint A, the object appears to be in front of the blue square. When the viewpoint is changed to Viewpoint B, the object appears to have moved to in front of the red square.

Use in distance measurement[]

By observing parallax, measuring angles, and using geometry, one can determine the distance to various objects. When this is in reference to stars, the effect is known as stellar parallax. The first measurements of a stellar parallax were made by Friedrich Bessel in 1838, for the star 61 Cygni.

Distance measurement by parallax is a special case of the principle of triangulation, where one can solve for all the sides and angles in a network of triangles if, in addition to all the angles in the network, the length of only one side has been measured. Thus, the careful measurement of the length of one baseline can fix the scale of a triangulation network covering the whole nation. In parallax, the triangle is extremely long and narrow, and by measuring both its shortest side and the small top angle (the other two being close to 90 degrees), the long sides (in practice equal) can be determined.

Parallax of the human eye[]

Parallax allows humans and other animals, such as cats, to see depth and perspective.

Binocular parallax[]

Binocular parallax is a binocular clue to depth perception, especially of near objects. Each eye views an object from a slightly different position, so the image seen by each is slightly different; fusion of the two images in the brain creates a perception of depth. [1]

If a person alternates between covering one eye and the other while fixating in the distance with a nearby object in front of them, the nearby object will appear to "jump" horizontally.

Parallax is used in simple stereo viewing devices, such as the View-Master used to view stereoscopic scenery in the form of two images taken from adjacent locations. The Apollo astronauts on the Moon knew how to take such stereo pairs, clicking two frames of the same object in locations shifted slightly horizontally with respect to each other.

A way to allow one or more people to simultaneously view a stereoscopic scene is to provide them with 3D Glasses. 3D glasses use various means (color, polarization, or timing) to deliver separate images to each eye, allowing the visual cortex to perceive parallax to reconstruct the scene in three dimensions.

Autostereograms exploit the effect of parallax to allow viewers to see 3D shapes in a single 2D image.

Monocular parallax[]

Monocular parallax is an important monocular clue to depth perception. As the head or the eye is moved from side to side, distant objects appear to move more slowly than do closer objects. [2]

Parallax and measurement instruments[]

If an optical instrument — telescope, microscope, theodolite — is imprecisely focused, the cross-hairs will appear to move with respect to the object focused on if one moves one's head horizontally in front of the eyepiece. This is why it is important, especially when performing measurements, to carefully focus in order to 'eliminate the parallax', and to check by moving one's head.

Also in non-optical measurements, e.g., the thickness of a ruler can create parallax in fine measurements. One is always cautioned in science classes to "avoid parallax." By this it is meant that one should always take measurements with one's eye on a line directly perpendicular to the ruler, so that the thickness of the ruler does not create error in positioning for fine measurements. A similar error can occur when reading the position of a pointer against a scale in an instrument such as a galvanometer. To help the user to avoid this problem, the scale is sometimes printed above a narrow strip of mirror, and the user positions his eye so that the pointer obscures its own reflection. This guarantees that the user's line of sight is perpendicular to the mirror and therefore to the scale.

In photography, one also talks about the parallax of a camera viewfinder: for nearby objects, a viewfinder mounted on top of the camera will show something different from what the lens 'sees', and people's heads may be cut off. The problem does not exist for the single lens reflex camera, where the viewfinder looks (with the aid of a movable mirror) through the same lens as is used for taking the photograph.

Photogrammetric parallax[]

Aerial photograph pairs, when viewed through a stereo viewer, offer a pronounced stereo effect of landscape and buildings. High buildings appear to 'keel over' in the direction away from the centre of the photograph. Measurements of this parallax are used to deduce the height of the buildings, provided that flying height and baseline distances are known. This is a key component to the process of Photogrammetry.

Lunar parallax[]

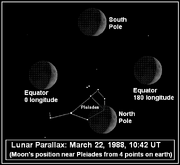

Example of lunar parallax: Occultation of Pleiades by the Moon

Jules Verne, From the Earth to the Moon (1865). "Up till then, many people had no idea how one could calculate the distance separating the Moon from the Earth. The circumstance was exploited to teach them that this distance was obtained by measuring the parallax of the Moon. If the word parallax appeared to amaze them, they were told that it was the angle subtended by two straight lines running from both ends of the Earth's radius to the Moon. If they had doubts on the perfection of this method, they were immediately shown that not only did this mean distance amount to a whole two hundred thirty-four thousand three hundred and forty-seven miles (94,330 leagues), but also that the astronomers were not in error by more than seventy miles (— 30 leagues)."

A primitive way to determine the lunar parallax from one location is by using a lunar eclipse. The full shadow of the Earth on the Moon has an apparent radius of curvature equal to the difference between the apparent radii of the Earth and the Sun as seen from the Moon. This radius can be seen to be equal to 0.75 degree, from which (with the solar apparent radius 0.25 degree) we get an Earth apparent radius of 1 degree. This yields for the Earth-Moon distance 60 Earth radii or 384,000 km. This procedure was first used by Aristarchus of Samos and Hipparchus, and later found its way into the work of Ptolemy.

Another way to use parallax to determine the distance to the Moon would be to take two pictures of the Moon at exactly the same time from two locations on Earth, and compare the position of the Moon relative to the visible stars. Using the orientation of the Earth, and those two points, and a perpendicular displacement, a distance to the Moon can be triangulated.

Solar parallax[]

After Johannes Kepler discovered his Third Law, it was possible to build a scale model of the whole solar system, but without the scale. To fix the scale, it suffices to measure one distance within the solar system, e.g., the mean distance from the Earth to the Sun or astronomical unit (AU). When done by triangulation, this is referred to as the solar parallax, the difference in position of the Sun as seen from the Earth's centre and a point one Earth radius away, i.e., the angle subtended at the Sun by the Earth's mean radius. Knowing the solar parallax and the mean Earth radius allows one to calculate the AU, the first, small step on the long road of establishing the size — and thus the minimum age — of the visible Universe.

A primitive way of determining the distance to the Sun in terms of the distance to the Moon was already proposed by Aristarchus of Samos: if the Sun is relatively close by, the first and last quarters of the Moon will not happen in time precisely in the middle between new and full moon. Unfortunately the method (which unrealistically assumes regular circular motion for the Moon) becomes progressively imprecise for solar distances much larger than the distance of the Moon, and Aristarchus obtained a nonsensical result. It is, however, in essence a parallax method.

It was proposed by Edmund Halley in 1716, that the transit of Venus over the solar disc be used to derive the solar parallax. And so it was done in 1761 and 1769. There is the famous story of the French astronomer Guillaume Le Gentil, who travelled to India to observe the 1761 event, but didn't reach his destination in time due to war. He stayed on for the 1769 event, but then there were clouds blocking the Sun...

The use of Venus transits was less successful than had been hoped due to the black drop effect.

Much later, the solar system was 'scaled' using the parallax of asteroids, some of which, like Eros, pass much closer to Earth than Venus. In a favourable opposition, Eros can approach the Earth to within 22 million kilometres. Both the opposition of 1901 and that of 1930/1931 were used for this purpose, the calculations of the latter determination being completed by Astronomer Royal Sir Harold Spencer Jones.

Also radar reflections, both off Venus (1958) and off asteroids, like Icarus, have been used for solar parallax determination. Today, use of spacecraft telemetry links has solved this old problem completely.

Stellar parallax[]

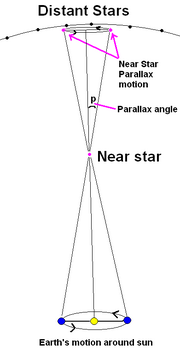

Stellar parallax motion

On an interstellar scale, parallax created by the different orbital positions of the Earth causes nearby stars to appear to move relative to the more distant stars. However, this effect is so small it is undetectable without extremely precise measurements.

The annual parallax is defined as the difference in position of a star as seen from the Earth and Sun, i.e. the angle subtended at a star by the mean radius of the Earth's orbit around the Sun. Given two points on opposite ends of the orbit, the parallax is half the maximum parallactic shift evident from the star viewed from the two points. The parsec is the distance for which the annual parallax is 1 arcsecond. A parsec equals 3.26 light years.

The distance of an object (in parsecs) can be computed as the reciprocal of the parallax. For instance, the Hipparcos satellite measured the parallax of the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, as .77233 seconds of arc (±.00242"). Therefore, the distance is 1/0.772=1.29 parsecs or about 4.22 light years (±.01 ly).

The angles involved in these calculations are very small. For example, .772 arcseconds is roughly the angle subtended by an object about 2 centimeters in diameter (roughly the size of a U.S. Quarter) located about 5.3 kilometers away.

Computation[]

The parallax in arc seconds

where

- au = astronomical unit = Average distance from sun to earth = 1.4959 · 1011 m

- d = distance to the star

Picking a good unit of measure will cancel the constants. Derivation:

- right triangle

- small angle approximation

- arcseconds

- parallax

- If the parallax is 1", then the distance is = 206264 au = 3.2616 lyr = 1 parsec (This defines the parsec)

- The parallax arcseconds, when the distance is given in parsecs

The fact that stellar parallax was so small that it was unobservable at the time was used as the main scientific argument against heliocentrism during the early modern age. It is clear from Euclid's geometry that the effect would be undetectable if the stars were far enough away; but for various reasons such a gigantic size seemed entirely implausible.

Measurements of the annual parallax as the earth goes through its orbit was the first reliable way to determine the distances to the closest stars. This method was first successfully used by Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel in 1838 when he measured the distance to 61 Cygni, and it remains the standard for calibrating other measurement methods (after the size of the orbit of the earth is measured by radar reflection on other planets).

In 1989, a satellite called "Hipparcos" was launched with the main purpose of obtaining parallaxes and proper motions of nearby stars, increasing the reach of the method ten-fold. Even so, Hipparcos is only able to measure parallax angles for stars up to about 1,600 light-years away — a little bit more than one percent of the diameter of our galaxy.

Dynamic or moving-cluster parallax[]

The open stellar cluster 'Hyades' (Rain Stars) in Taurus extends over such a large part of the sky, 20 degrees, that the proper motions as derived from astrometry appear to converge with some precision to a perspective point north of Orion. Combining the observed apparent (angular) proper motion in seconds of arc with the also observed true (absolute) receding motion as witnessed by the Doppler redshift of the stellar spectral lines, allows us to estimate the distance of the cluster and its member stars in much the same way as using annual parallax.

Dynamic parallax has sometimes also been used to determine the distance to a supernova, when the optical wave front of the outburst was seen to propagate through the surrounding dust clouds at an apparent angular velocity, when we know its true propagation velocity to be the speed of light.

The scale of the Universe[]

All these various astronomical parallax methods allow us to establish the first rungs on the cosmic scale ladder, out to a few hundred light years. Beyond that, other methods must be taken into use: e.g., "spectroscopic parallaxes" — not really parallaxes at all. It is a prototype of a "standard candle" method, where we observe the apparent brightness of an object we know, based on some physical theory, the true brightness of. For groups of stars we have the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram which allows us to derive a star's absolute brightness or magnitude from its spectral type. The observed (apparent) brightness or magnitude being , we can then derive its parallax by

called "spectroscopic parallax".

Further methods, mostly of the standard candle variety, are the variable stars called Cepheids — the absolute brightness of which depends on their observed period of variation —, supernova brightnesses, globular cluster sizes and brightnesses, complete galaxy brightnesses etc. These are all much more uncertain as they are not based on simple geometry. Yet, parallaxes are the basis of everything, as they allow the calibration of these more uncertain methods in the Solar neighbourhood.

A very modern method which is not a traditional parallax method but also geometric in nature, is "gravitational lensing parallax". It depends on observing the differential time delay of brightness variations from a remote quasar reaching us by two different paths through the gravitational field or "lens" of a foreground galaxy. If the redshifts of both the quasar and the foreground galaxy are known, one can show that the absolute distances of both are proportional to the differential delay, and can in fact be calculated given also the geometry of the gravitational lens on the celestial sphere.

All these independent techniques aim at determining Hubble's constant, the constant describing how the redshift of galaxies, due to the Universe's expansion, depends on these galaxies' distance from us. Knowing Hubble's constant again allows us to determine, by simply running the film of the cosmic expansion backwards, how long ago it was when all these galaxies were collected in a single point -- the Big Bang. Current knowledge puts this at some 14.7 billion years ago, but with considerable uncertainty and dependence on various model assumptions.

Parallax as a metaphor[]

In a philosophic/geometric sense: An apparent change in the direction of an object, caused by a change in observational position that provides a new line of sight. The apparent displacement, or difference of position, of an object, as seen from two different stations, or points of view. In contemporary writing a parallax can also be the same story, or a similar story from approximately the same time line, from one book told from a different perspective in another book. The word and concept of "parallax" feature prominently in James Joyce's 1922 novel, Ulysses. Orson Scott Card also used this term when referring to Ender's Shadow as compared to Ender's Game.

See also[]

- Disparity(Brain)

- Triangulation, wherein a point is calculated given its angles from other known points

- Trilateration, wherein a point is calculated given its distances from other known points

- Trigonometry

Sources[]

External links[]

- Java applet demonstrating stellar parallax

- BBC's Sky at Night programme: Patrick Moore demonstrates Parallax using Cricket. (Requires RealPlayer)

- Simple method of using binocular parallax to estimate distances outdoors

- Elementary calculation of solar parallax using 2004 Venus transit data (algebra and trig only)

bg:Паралакс ca:Paral·laxi cs:Paralaxa da:Parallakse de:Parallaxe et:Parallaks es:Paralaje eo:Paralakso fr:Parallaxe io:Paralaxo he:היסט nl:Parallax pt:Paralaxe ru:Параллакс sk:Paralaxa fi:Parallaksi sv:Parallax zh:视差

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |