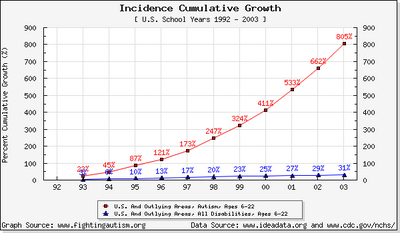

The number of reported cases of autism has increased dramatically over the past decade.

The prevalence, incidence or number of children diagnosed with autism may have increased significantly in recent years,[1][2] raising the question of whether extrinsic factors might be involved. As well as the incidence, the cause of any alteration in autism incidence is unclear. Various authors have speculated that genetic causes, pollution, food additives, or childhood vaccinations may play roles. Other speculation attributes increased diagnoses to screening, better recognition and even a form of collective hysteria. Changes in diagnostic categories in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders affect the numbers diagnosed as autistic, especially changes set out in DSM-III-R,[3] and DSM-IV [4].

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Clinical: Approaches · Group therapy · Techniques · Types of problem · Areas of specialism · Taxonomies · Therapeutic issues · Modes of delivery · Model translation project · Personal experiences ·

Caveats[]

Few mainstream scientists view the concept of an autism "epidemic" as useful and most focus on genetic, not bacterial, viral or man-made causes. Many attribute the dramatic rise in autism rates to more effective and inclusive diagnostic criteria and detection tools, noting that the diagnosis of autism was only created in the 1940s and the science around it is still only developing. Neither is there agreement within the autistic community. The autism rights movement vehemently disputes that any increase in diagnoses be labelled an 'epidemic', as this may imply that autism is a disability or disease. Hence the remainder of this article is built on a proposition challenged by a portion of the autistic community and the majority of scientists involved.

Autism prevalence[]

While the number of diagnoses related to autism has increased in recent decades, public health organizations and researchers have not yet determined whether:

- There is an actual increase in the incidence of autism, or whether

- More incidents of autism are being reported now, as a result of increased awareness of the disorder

- The diagnosis is being applied more broadly than before as a result of the changing definition of the disorder

- There is ongoing substitution of the "autism" label for less palatable designations such as mental retardation

- The magnitude of any increase warrants urgent and/or drastic measures

Whether the true incidence of autism had been increasing was quite unclear as recently as 1999[5]. Nevertheless, an increasing prevalence of autism diagnoses has sparked concerns, especially among parents, which in turn has lead to the initiation of a number of new treatment programs, advocacy groups and support programs. For example, Microsoft became the first major US corporation to offer employees insurance coverage for the cost of behavioral training for their autistic children in 2001, due to the high prevalence among the children of its employees.

Parent advocacy groups, such as Safe Minds, A-CHAMP and Generation Rescue, object to public health agencies' reservations about any urgent action, pointing out that if estimates of the increasing prevalence are true, several of the world's governments may be confronted with a catastrophic health crisis with deep humanitarian and economic implications. They are calling for increased research into environmental factors that might cause or contribute to autism, increased research into therapies and possible cures to treat autism, and greater funding of programs to help autistic people learn to live with their disorder.

In the absence of a universally accepted etiology of autism, many parents, health professionals, politicians and others are demanding further independent study into a number of possible causes for the increase in diagnosis. For example, there is demand for research into a possible causal connection between autism and the policy of universal, compulsory vaccination schedules. This demand reflects a highly controversial debate on the risks and benefits of vaccinations, pitting the medical community and public health agencies against a large proportion of parents (in California, one third of parents of children on the spectrum — see 'vaccine theories' below) and a relatively small group of physicians. The problem is exacerbated by a cadre of plaintiffs' lawyers who promote anti-vaccine theories in support of contingent-fee litigation against vaccine manufacturers in the United States. In one notorious example, the Lancet was forced to retract an attack on vaccines by Andrew Wakefield.

Australia[]

Australia is apparently experiencing a surge in autism spectrum disorders, where a ten-fold rise in diagnoses have been made in the past decade.[6] The Australian Education Department reported a 276 percent jump in students with autism spectrum disorder between 2000 and 2005. As of 2005, a total of 23,083 Victorian students were placed in school disability and language disorder programs, rising 74 per cent from 13,257 students in 2000.

China[]

In a July, 2005, interview Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. stated that, "six years ago, autism was unknown in China. We started giving them our vaccines in 1999. Today there's 1.8 million cases of autism in China."[7] Shanghai alone has over 10,000 known autistic children.[8] However, this seems to conflict with a 1997 study, in China, about teaching Chinese to autistic children, [9] as well as a 1991 study of a Chinese "calendar savant". [10]

Denmark[]

A study from Denmark was published in November 2002, attracting substantial attention. The incidence of autism reported in the study appeared lower than the prevalence reported in the US and other countries. In Denmark, an incidence rate of 1 out of 727 (or 738 out of 537,303) was reported, far less than estimates of up to 1 in 86 among primary school children in the United Kingdom and around 1 out of 150 children in the US.

Danish authorities discontinued use of thimerosal in 1992 [11], but cite studies showing a continued increase in the incidence of autism as evidence that thimerosal was not a contributing factor. However, according to Kennedy, "before banning thimerosal, Denmark registered only autistics who were hospitalized — one fifth of the afflicted populations. After the withdrawal of thimerosal, Denmark began counting out-patient autistics in its registries. The resulting spike in raw numbers therefore made it appear that autism rates actually increased after the withdrawal of thimerosal."[12]

Japan[]

A study released in early 2005 was the first to examine autism trends before and after the 1993 withdrawal of MMR from the Japanese market, inclusive of children who had not had the three-in-one jab. The MMR was withdrawn in Japan in a crisis of confidence after the mumps component was linked to meningitis. The study's authors reported 48 and 86 cases per 10,000 children in two sequential years prior to withdrawal, doubling to 97 and 161 per 10,000 afterwards in two seqeuential years afterwards. [13]

Dr. Wakefield has noted the specific year to year data shows a dip in autism diagnoses after Japanese public confidence fell in the MMR specifically, and vaccinations generally. Wakefield notes autism rates had risen to 85.9 per 10,000 for children born in 1990, but declined to 55.8 per 10,000 for children born in 1991 when MMR uptake declined before the MMR vaccine's withdrawal. Autism rates have steadily increased since that time, after the Japanese public began to accept the notion of three separate vaccines and refinements to diagnostic criteria.[14]

Russia[]

In response to a study performed in 1977, Russia banned thimerosal from children's vaccines by 1985. Despite this, the Russian autism rate did not change for at least a decade.[15]

United Kingdom[]

According to Vaccination News, one in eighty-six primary school children in the United Kingdom has autism, compared with one in 2,200 in 1988.[16] Another estimate of the UK incidence rate came from the National Autistic Society, which estimated autism spectrum disorders in the total population to be one in 110. A 2001 review, by the Medical Research Council, yielded an estimate of one in 166 in children under eight.

According to statistics cited by Bernard Rimland, the autism rate in the UK suddenly spiked after the first introduction of the MMR vaccine in 1989, just as it had after the MMR's introduction in the US in the late 1970s.[17]. This is not consistent with evidence published in the British Medical Journal.[18]

Substantial funds (over £3 million) were spent in the UK on a pro-MMR campaign.[19] Concerted efforts have been made by the British government and pharmaceutical industry interests to negate the widely criticized 1998 study, led by Dr. Wakefield, that showed a consistent set of bowel disorders among a dozen autistic children.[20] The study authors also suggested the need for further studies into the apparent link between MMR and autism, although 10 of Wakefield's co-authors retracted the recomendation six years later. The 2002 Danish epidemiological study was a consideration in the 2004 US Institute of Medicine (IOM) Special Committee decision, which concluded that a connection between MMR vaccination and autism did not exist.

Scotland[]

Among the predominantly industrialized nations affected by reports of an autism epidemic, Scotland is frequently cited as a possible epicenter. The number of schoolchildren diagnosed with autistm in Scotland has surged significantly over the past six years, with an increase of more than 600 per cent among secondary school students. In 1999, there were 114 children with autism diagnoses in state secondaries, compared with 825 in 2005. Over the same period, the number of autistic youngsters in primary schools more than quadrupled, from 415 to 1,736.[21]

United States[]

After years of substantial annual increases, provisional data from the US Department of Education show a significant decrease in the number of new autism diagnoses recorded among children 3 to 5 years old. There were 1,451 new cases in 2001-2002; 1,981 in 2002-2003; 3,707 in 2003-2004; and 3,178 in 2004-2005, a drop of 529 new cases, or 14%.[22]

According to a recent 'conservative' estimate, there are approximately 500,000 autistic spectrum cases in the United States, including perhaps as many as 1 in 150 children. "With eighty percent of autistic Americans under the , the dramatic impact of this crisis will be felt by taxpayers in the coming years when these autistic children become adults," says Anne McElroy Dachel of the National Autism Association.

Autism is the fastest growing population of special needs students in the US, having grown by over 900% between 1992 and 2001, according to data from the United States Department of Education. In 1999, the autism incidence rate in the US was generally cited at 4.5 cases per 10,000 live births. By 2005, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates one of every 250 babies is born with autism, or 40 cases per 10,000.

The rising enrollments in special education classes were examined in a 2006 Pediatrics journal article. During the period between 1994 and 2003, as autism diagnoses rose, diagnosis of mental retardation and learning disabilities dropped sharply. This study also found that prevalence data taken from special education enrollment revealed numbers of diagnoses significantly less than epidemiologic estimates.[23]

As many as 1.5 million Americans may have some form of autism, including milder variants, and the number is rising. Epidemiologists estimate the number of autistic children in the US could reach 4 million in the next decade.[24]

California[]

California is considered to have the best reporting system for autism in the US. According to data released in late 2005 by the California Department of Developmental Services (DDS), new cases — of professionally diagnosed full syndrome DSM IV autism — entering the DDS system indicated a decline, from 734 new cases during the second quarter of 2005 to 678 new cases during the third quarter of 2005, a 7.5% decline in one quarter.

As of August 1993, a total of only 4,911 cases of autism had been logged in DDS's client-management system, a number excluding milder autism spectrum disorders, such as Asperger's syndrome. By April 29, 1999, the DDS reported a State-wide incidence rate of about 15 to 20 per 10,000, triggering alarms about the staggering increase.

As of 2005, the DDS reported a total of 28,046 cases, but that the rate of increase peaked in 2002 and has dropped slightly since then. According to data released by DDS in January, 2006, the number of new cases of professionally diagnosed full syndrome autism entering California's developmental services system in 2005 was the smallest since 2001. The DDS year end report documents that, during 2005, California added 2,848 new cases of autism to its system. Not since 2001, when 2,725 new cases were added, has California added fewer new cases of full syndrome autism to its system. Ever since the record year of 2002, there has been a slow, steady decline in the number of new autism cases entering the 37-year old DDS system, even though levels have still not yet reached the 1 in 166 reported by population-based studies.

The use of the term "New Cases" has come into question and DDS itself has documented that "New Cases" should not be calculated as the difference in the numbers between quarters [25]. The total caseload handled by the state continues to increase at a pace much higher than population growth, but the recent trend points to a decrease in the caseload increase per quarter. The decline has been speculated to coincide with vaccines containing thimerosal being phased out in recent years. It could also indicate that the awareness curve is starting to level off. It has also been pointed out that the caseload does not yet meet the levels found in population studies.

Critics of the vaccine theory point out that if vaccine injury was the cause of the increase in autism spectrum diagnoses, a sharp decline in new cases should be expected, and eventually a decrease in total caseload. In contrast, if the better diagnostic awareness theory is correct, a gradual decline in new cases should be expected until caseload increase reaches population growth levels.

According to a report by the DDS, Autistic Spectrum Disorders, Changes in the California Caseload: 1999-2002, the rate of children diagnosed with full-syndrome autism in California nearly doubled between 1999 and 2002, from 10,360 to 20,377. The report stated, "(B)etween Dec. 31, 1987, and Dec. 31, 2002, the population of persons with full-syndrome autism has increased by 634 percent."

California's increase in childhood autism was not due to flawed diagnoses, according to a 2002 study led by University of California, Davis pediatric epidemiologist Robert Byrd. 1,685 newly diagnosed autistic children had entered the state's regional center system the previous year, marking a 273 percent increase over an 11-year period from 1988 to 1999. The data again included only children with classic autism, discounting those with PDD-NOS, Asperger's, etc. "The sheer complexity of this phenomenon prevents any clear conclusions," the report stated. "What we do know is that the number of young children coming into the system each year is significantly greater than in the past."

"It's a dramatic report, but what's shocking is that it's not clear what the cause is," said Dr. Thomas Anders, a child psychiatrist and acting director of the M.I.N.D. Institute at the University of California, Davis. Yet the report statistics were very "conservative", according to Rick Rollens, former secretary of the California State Senate and father of Russell, who has been diagnosed with autism, adding "It does not include people who are not part of the regional system, and it is estimated that (the regional system is) really serving only half the people with developmental disabilities," said Rollens.

Granite Bay cluster[]

By 1999, in Granite Bay, California, 22 of the 2,930 children enrolled in grades K-6 were autistic.

Silicon Valley cluster[]

A 2002 BBC article indicated that one in 150 children in the region had an autistic spectrum disorder. A 2001 article in Wired suggested that the cluster is a result of a link between autistic disorders and computer skills.

Connecticut[]

The number of autistic children educated at public expense in Connecticut has increased 325 percent since 1996, according to the State Department of Education. Governor M. Jodi Rell included a 38 percent increase, to $25.5 million, in the State's budget, for reimbursement to local schools for special education costs.

Stratford cluster[]

In Stratford, Connecticut the number of children diagnosed with autism who receive special education services has increased 400 percent since 1996. Although only 20 children currently in the school system have autism, the cost for their education may exceed $750,000.

Hawaii[]

Rick Rollens, a co-founder of the M.I.N.D. Institute, found an autism cluster in a small, isolated area on the east shore of Oahu, Hawaii, in part consisting of a dozen native Hawaiian children with regressive autism, all suffering from gastrointestinal problems, sleep disorders, gluten and casein digestion problems, autoimmune problems, yet having no family history of autism or any other developmental disability.[26]

New Jersey[]

New Jersey also has a high number of autistic children. This may be because, like California, New Jersey boasts many scientific research and high technology industry enclaves, which dominate the state's economy. A significant portion of the autistic children in New Jersey, intriguingly, were either born in other States or have parents from another State; many more autistic children may have moved to New Jersey from other states specifically because of its well known special education system.

Brick Township cluster[]

An 'autism cluster' was identified in Brick Township, New Jersey, in 1999. Parents attributed the diagnoses to environmental pollution, but investigators could not confirm the suspicions. The town had about 40 cases among 6,000 children.

Pennsylvania[]

Governor Edward G. Rendell has dedicated $3 million to help Pennsylvania enhance efforts to better diagnose and develop treatment procedures for the 74,000 Pennsylvanians diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders.[27]

Amish anomaly[]

An apparent anomaly among Amish populations was reported in 2005. Although a formal study has not yet been conducted, efforts to assess the prevalence of autism in the Amish community turned up only a very few cases. About 22,000 Amish live in Lancaster County, yet only three or four Amish with autism have turned up thus far in an informal survey of Lancaster County, whereas dozens would be expected at the 1-in-166 prevalence in society at large. "You'll find all the other stuff, but we don't find the autism," according to Dr. Frank Noonan, a Lancaster County family doctor, adding "We're right in the heart of Amish country and seeing none."

In June, 2005, William F. Raub, of the Department of Health and Human Services, suggested the possibility of launching studies of the Amish in response reports of a low prevalence of autism in that community.[28]

Since vaccinations are virtually unheard of in the Amish, these preliminary findings have sparked further speculation about the vaccine-autism link. However, note is made of potential for substantial confounding with other aspects of Amish lifestyle and genetic homogeneity.

Proposed causes[]

- For more details on this topic, see Causes of autism.

When autism was first described and reported by Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger in the early 1940s, nothing was known about what was causing the previously unrecognized syndrome. The increasing numbers have led to many hypotheses.

New diagnostics[]

When the rising prevalence of autism spectrum disorders sparked research into the trend in the late 1990s, the medical establishment primarily attributed the increase to improved diagnostic screening or changes in the definition of autism. In 1994, the fourth major revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) was published [29]. It included substantially updated criteria for the diagnosis of autism and autism spectrum disorders.[30] Professional medical associations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, say that this revision was an important factor in increasing the apparent prevalence of autism. A 2005 study by Mayo Clinic researchers found that sharp increases in autism diagnoses have followed revisions in DSM criteria and changes in funding for special education programs. [31].

Much of the prevalence increase could be explained through increased awareness and knowledge about autistic disorders in the part of parents and pediatricians. The implications of this view are that children in the past were likely diagnosed as having a different condition, or not diagnosed at all. Several potential misdiagnosis have been cited, such as mental retardation, learning disability [32] and childhood schizophrenia [33]. High functioning autistic children are sometimes misdiagnosed ADHD [34] and it's possible such misdiagnosis were more common in the recent past. Another possible contributing effect is that of giving a diagnosis of Autism to children who are not primarily autistic, e.g. those with Fragile-X Syndrome (with characteristics that fit the criteria for autism) and even Down's Syndrome (which may be comorbid with autism.) Dr. Fred Volkmar, an autism researcher from Yale has said that "Autism is a kind of fashionable diagnosis" [35].

It has been pointed out that updated diagnostic criteria, more awareness, and so on, would only account for increases in diagnosis of high-functioning autism, and that there's evidence of prevalence increases in so-called classic autism. But this reasoning is not necessarily correct. If criteria on one end of the spectrum has shifted, it is not unreasonable to suppose that it has shifted across the spectrum. Anecdotal accounts suggest that, in the past, diagnoses were not sought even for late-talking children. It is unlikely that today, in the industrialized world, a late-talking child would be left undiagnosed after entering the school system. A recent rash of late diagnosis and self-diagnosis of Asperger's Syndrome in adults (perhaps due in part to the success of the world wide web) supports this observation. Adults currently receiving a diagnosis of Asperger's Syndrome could have been late-talkers as children, in which case a diagnosis of autism would have been more appropriate, had they been diagnosed then.

Data from the California Department of Developmental Services (DDS) show that autistic client characteristics have changed over time. In particular, the proportion of autistic clients with mental retardation has dropped gradually since 1992 and continued to drop as of 2006. This has been cited as evidence of a broadening criteria effect.

Genetic predisposition and vulnerability[]

High technology enclaves have been noted repeatedly for having relatively high prevalence rates of autism spectrum disorders. People with highly analytical skills and mathematical capabilities, who excel in certain industries, despite lacking basic social skills, are often labeled as geeks or nerds.

There is evidence that autistic individials have a higher proportion of engineers as close family members than the rest of the population.[36] The explanation offered is that persons with a broader autistic phenotype are driven to professions where human interaction is not as important as working with objects and concepts.

Assortative mating[]

According to Simon Baron-Cohen, the genetics that contribute to autism might actually result in part from assortative mating of two particular types of parents, with certain systematizing cognitive traits, both contributing genes. Baron-Cohen believes that "it has become easier for systemizers to meet each other, with the advent of international conferences, greater job opportunities and more women working in these fields." [37]

Assortative mating has not been demonstrated in humans, however. The spouses of identical twins tended to find the other twin annoying rather than attractive.[38]

Earlier preschool entrance[]

There is evidence that children are entering preschool earlier than in the past, at least in the industrialized world; a trend fueled mostly by the early education movement. Following a reasoning along the lines of the 'increased awareness' theory, earlier preschool entrance could in part explain a rise in diagnosed cases of autism for the following reasons:

- Preschool provides an environment where a toddler's behavior can be compared to that of their peers for extended periods of time. At the age of 2 or 3 autistic children start to show marked behavioral differences and a portion of these children may have otherwise gone undiagnosed after they develop certain skills some time later.

- Teachers can alert parents based on their past experience with other children.

But earlier preschool entrance could be having an effect that goes beyond increased awareness. It is believed that preschool can be stressful to young children, particularly when they first enter.

Autistic individuals are known to be prone to stress. Stress and social pressure in some autistic children can trigger 'shutdowns'.[39][40]. Stress has also been associated with seizures, and seizures in autistic children have been associated with 'regression'.[41] A plausible conclusion from this is that increased early stress could be amplifying the observed autistic traits of some children.

There is also a belief that stress can cause regressions in the development of non-autistic children in general.[42]. Some parents report observing developmental regressions that they attribute to early preschool entrance.[43][44]

Autistic author Jasmine O'Neill has said that school is the "end of bliss" for autistic children. Anecdotal accounts of this nature have been used to make dubious links between other types of occurrences in a child's life and 'regression'.

There are two studies that claim extended time in preschool can impair social development.[45]

Vaccination[]

The measured increases also began a few years after some significant increases to the vaccination schedule. This fact has lead some individuals to conclude that vaccines cause autism.

See also[]

References[]

^ Shattuck PT. Diagnostic substitution and changing autism prevalence. Pediatrics. 2006 Apr;117(4):1438-9. PMID 16585346

- CPA-APC.org - Diagnosis and Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders Lee Tidmarsh, MD, Fred R Volkmar, MD, The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 48 pp 517–525, 2003

- NIH.gov - 'The changing prevalence of autism in California', L.A. Croen, J.K. Grether, J Hoogstrate, S Selvin, Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders Vol 32, No 3, pp 207-15, June, 2002

- NIH.gov -'The epidemiology of autistic spectrum disorders: is the prevalence rising?', Lorna Wing, D. Potter, Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev, Vol 8, No 3, pp 151-61, 2002

- NIH.gov - 'Prevalence of autistic spectrum disorders in Lothian, Scotland: An estimate using the 'capture-recapture' technique', M.J. Harrison, A O'Hare, H. Campbell, A. Adamson, J McNeillage, Arch Dis Child. May 10, 2005

- NIH.gov - 'The incidence of autism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-1997: results from a population-based study', W.J. Barbaresi, S.K Katusic, R.C. Colligan, A.L. Weaver, S.J. Jacobsen, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, Vol 159, No 1, pp 37-44, January, 2005

- NEJM.org - 'A Population-Based Study of Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccination and Autism' Kreesten Meldgaard Madsen, MD, Anders Hviid, MSc, Mogens Vestergaard, MD, Diana Schendel, PhD, Jan Wohlfahrt, MSc, Poul Thorsen, MD, Jørn Olsen, MD, and Mads Melbye, MD, New England Journal of Medicine, Vol 347, No 19, pp1477-1482, November 7, 2002

- ParentAdvocates.org - 'MMR – Autism Epidemiological Studies: Just a distraction', F. Edward Yazbak, MD, FAAP

- Unraveling the Mystery of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorder : A Mother's Story of Research & Recovery, Karen Seroussi, Broadway Publishing, 2002

External links[]

Background issues on autism epidemiology[]

- About.com - 'The Puzzling Reality of an Autism Epidemic', Floyd Tilton

- NeuroDiversity.com - 'Prevalence of Autism'

- NeuroDiversity.com - 'The "Autism Epidemic" & Real Epidemics' (and reply from the M.I.N.D. Institute Director, confirming inappropriate use of "epidemic" to describe autism prevalence'), Kathleen Seidel

- NIDs.net - (press release) Neuro Immune Dysfunction Syndromes Medical Advisory Board and Research Institute (March 31, 2002)

- PediatricServices.com - 'The Autism Epidemic'

- ScienceDaily.com - 'The Age of Autism: What epidemic?', Dan Olmsted, Science Daily (August 1, 2005)

- ScienceDaily.com - 'The Age of Autism: The Amish anomaly', Dan Olmsted, Science Daily (April 18, 2005)

- Scoop.co.nz - 'Pharma's Poisoned Generation', Evelyn Pringle, Scoop Independent News (November 29, 2005)

- SFGate.com - 'State autism rate confounds experts: 273% increase in 11-year span', Katherine Seligman, San Francisco Chronicle (October 18, 2002)

- TheAge.com.au - 'Number of disabled students soars' Chee Chee Leung The Age (April 26, 2005)

- TMCNet.com - 'Parents say autism is an issue across the globe' (January 11, 2006)

Attribution to vaccines suggested or alleged[]

- Autisme.net - 'The Autism Explosion', Bernard Rimland, Ph.D.

- AutismCanada.org - 'The Autism Epidemic is Real, and Excessive Vaccinations are the cause' Bernard Rimland, PhD (July 14, 2003)

- Independent-Media.tv - 'UK Psychologist Says Definite Link Between Vaccines & Autism', Evelyn Pringle (March 7, 2005)

- InformedChoice.info - 'MMR vaccine and the autism epidemic: In a compulsory inoculation program, it is the responsibility of the developers, promoters and enforcers to prove safety and efficacy'

- MSNBC.com - 'A coverup for a cause of Autism? RFK Jr. explans how ingredient in vaccines may have contributed to spread' (interview transcript), MSNBC (June 22, 2005)

- WorldNetDaily.com - 'Vaccines fueling autism epidemic? Report: U.S. infants exposed to mercury beyond EPA, FDA limits' Kelly Patricia O'Meara (June 9, 2003)

- VaccinationNews.com - 'Autism Prevalence'

- Sue Bennett, Autism Immunization Pol, url=http://www.autismcoach.com/autism immunization poll.htm

- Mark Geier, M.D., Ph.D., David A. Geier, B.S.| title=American Physicians and Surgeons, March 10, 2006

- Robert Kennedy, Jr., Autism Epidemic, Rolling Stone Magazine, June 14, 2006.

Attribution to vaccines uncertain or refuted[]

- AAP.org - 'Study Fails to Show a Connection Between Thimerosal and Autism', American Academy of Pediatrics (May 16, 2003)

- Autism-RxGuideBook.net - 'A Population-Based Study of Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccination and Autism', Kreesten Meldgaard Madsen, MD, Anders Hviid, MSc, Mogens Vestergaard, MD, Diana Schendel, PhD, Jan Wohlfahrt, MSc, Poul Thorsen, MD, Jørn Olsen, MD, and Mads Melbye, MD

- NationalAcademies.org - 'MMR Vaccine and Thimerosal-Containing Vaccines Are Not Associated With Autism, IOM Report Says'

- MMRtheFacts.nhs.uk - MMR News and Research from the British National Health Service

Genetic vulnerability and the 'geek syndrome'[]

- BBC.co.uk - 'Autism link to "geek genes"' (August 14, 2002)

- Edge.org - 'The Assortative Mating Theory: A Talk with Simon Baron-Cohen' (April 6, 2005)

- Wired.com - 'The Geek Syndrome: Autism - and its milder cousin Asperger's syndrome - is surging among the children of Silicon Valley. Are math-and-tech genes to blame?' Steve Silberman Wired (December, 2001)

- WUStL.edu - 'Autism's genetic structure offers insights' Jim Dryden Washinghton University Record (May 13, 2005)

Pervasive developmental disorders / Autism spectrum | |

|---|---|

| Main |

Causes • Comorbid conditions • Epidemiology • Heritability • Sociological and cultural aspects • Therapies |

| Diagnoses |

Asperger syndrome • Autism • Childhood disintegrative disorder • PDD-NOS |

| Related conditions |

Epilepsy • Fragile X syndrome • High-functioning autism • Hyperlexia • Rett syndrome |

| Controversies |

Autism rights movement • Autistic enterocolitis • Chelation • MMR vaccine • Neurodiversity |

| Lists |

Autism-related topics • Further reading on Asperger syndrome • List of fictional characters on the autistic spectrum |

| Groups |

Aspies For Freedom • Autism Network International • Autistic Self Advocacy Network |

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |