m (fixing dead links) |

|||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{PersonPsy}} |

{{PersonPsy}} |

||

| + | {{expert}} |

||

| − | '''Creativity''' is a human mental phenomenon based around the deployment of [[mental]] [[skills]] and/or conceptual [[tools]], which, in turn, originate and develop [[innovation]], [[inspiration]], or insight. |

||

| + | {{Main|The psychology of creativity}} |

||

| + | {{Main|The teaching of creativity}} |

||

| − | ==Scope== |

||

| − | For some people, the word ''creativity'' conjures up [[Association (psychology)|associations]] strictly with [[art | artistic endeavours]] and with the [[writing]] of [[literature]]. Some others have also linked creativity with moments of sudden [[science|scientific]] or [[engineering]] insight since at least the time of [[Archimedes]] in [[Ancient Greece]]. |

||

| + | {{Main|The skills approach to creativity}} |

||

| − | [[Pop psychology]] sometimes associates it with [[cerebral hemisphere | right or forehead brain activity]] or even specifically with [[lateral thinking]]. |

||

| + | {{Main|Creativity in clinical practice}} |

||

| − | Within the different modes of artistic expression, one can postulate a continuum extending from "[[interpretation]]" to "innovation". Established [[art movements | artistic movement]]s and [[genre]]s pull practitioners to the "interpretation" end of the scale, whereas original thinkers strive towards the "innovation" pole. Note that we conventionally expect some "creative" people (dancers, actors, orchestral members, etc.) to perform (interpret) while allowing others (writers, painters, composers, etc.) more freedom to express the new and the different. |

||

| + | {{Main|The physiological basis of creativity}} |

||

| − | Since the time of [[Graham Wallas]] and his work ''[[Art of Thought]]'', published in [[1926]], some have considered creativity a legacy of the [[evolution|evolutionary]] process, which allowed humans to quickly adapt to rapidly changing environments. |

||

| − | Today, creativity forms in some eyes the core activity of a growing section of the [[global economy]] — the so-called "[[creative industries]]" — capitalistically generating (generally non-tangible) [[wealth]] through the [[creation]] and [[exploitation]] of [[intellectual property]] or through the provision of [[creative services]]. |

||

| + | '''Creativity''' is a mental and social process involving the generation of new [[idea]]s or [[concepts]], or new associations of the creative mind between existing ideas or concepts. An alternative conception of creativness is that it is simply the act of making something new. |

||

| − | The word "creativity" can convey an implication of constructing [[novelty]] without relying on any existing constituent components (''ex nihilo'' - compare [[creationism]]). Contrast alternative theories, for example: |

||

| + | From a scientific point of view, the products of creative thought (sometimes referred to as [[convergent and divergent production|divergent thought]]) are usually considered to have both originality ''and'' appropriateness. |

||

| − | * artistic [[inspiration]], which provides the transmission of [[Vision (religion)|vision]]s from divine sources such as the [[Muse]]s; a taste of the Divine. Compare with [[invention]]. |

||

| + | Although intuitively a simple phenomenon, it is in fact quite complex. It has been studied from the perspectives of [[behavioural psychology]], [[social psychology]], [[psychometrics]], [[cognitive science]], [[artificial intelligence]], [[philosophy]], [[history]], [[economics]], [[business]], and [[management]], among others. The studies have covered everyday creativity, exceptional creativity and even [[Artificial Creativity|artificial creativity]]. Unlike many phenomena in science, there is no single, authoritative perspective or definition of creativity. And unlike many phenomena in psychology, there is no standardized measurement technique. |

||

| − | * artistic [[evolution]], which stresses obeying established ("classical") rules and imitating or [[appropriation (art) | appropriating]] to produce subtly different but unshockingly understandable work. Compare with [[crafts]]. |

||

| + | Creativity has been attributed variously to divine intervention, [[cognitive]] processes, the [[social]] environment, [[trait theory|personality traits]], and [[Randomness|chance]] ("accident", "[[serendipity]]"). It has been associated with [[genius]], [[mental illness]] and [[humour]]. Some say it is a [[trait (biological)|trait]] we are born with; others say it can be taught with the application of [[creativity techniques|simple techniques]]. |

||

| − | ==Dimensions of creativity== |

||

| − | Creativity can be assessed on several dimensions: |

||

| + | Although popularly associated with [[art]] and [[literature]], it is also an essential part of [[innovation]] and [[invention]] and is important in professions such as [[business]], [[economics]], [[architecture]], [[science]] and [[engineering]]. |

||

| − | * '''Intellectual leadership'''. Creative thinkers are able to create new and promising theories or exciting trends which inspire others to follow up; in essence starting a movement, school of thought or trend. |

||

| + | Despite, or perhaps because of, the ambiguity and multi-dimensional nature of creativity, entire creative industries have been spawned from the pursuit of creative ideas and the development of [[creativity techniques]]. |

||

| − | * '''Sensitivity to problems'''. Being able to identify problems that challenge others and open up a new field of thought is a mark of creative thinking. |

||

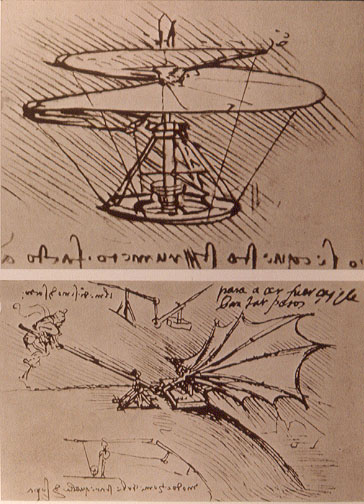

| + | [[Image:Leonardo da Vinci helicopter and lifting wing.jpg|frame|right|[[Leonardo Da Vinci]] is well known for his creative works.]] |

||

| − | * '''Originality'''. Creative thinkers are able to find ideas or solutions with which no one else has been able to come up. Patents are (supposedly) given out only to original ideas. |

||

| + | Creativity has been associated with [[right brain|right or forehead brain activity]] or even specifically with [[lateral thinking]]. |

||

| − | * '''Ingenuity'''. Ingenious solutions are able to solve problems in a neat and surprising way or which also reflect a new perspective at looking at the problem. |

||

| + | Some students of creativity have emphasized an element of [[Randomness|chance]] in the creative process. [[Linus Pauling]], asked at a public lecture how one creates [[theory|scientific theories]], replied that one must endeavor to come up with ''many'' ideas — then discard the useless ones. |

||

| − | * '''Unusualness'''. Creative thinkers are able to see the remote associations between ideas. When word association tests are given, people in highly creative literary fields like poets give a higher proportion of unique responses. |

||

| + | Another adequate definition of creativity is that it is an "assumptions-breaking process." Creative ideas are often generated when one discards preconceived assumptions and attempts a new approach or method that might seem to others unthinkable. |

||

| − | * '''Usefulness'''. Solutions or ideas that are also practical are also considered more creative as the creator is able to meet the constraints of the problem while at the same time producing unusual and original solutions. |

||

| + | ==Distinguishing between creativity and innovation== |

||

| − | * '''Appropriateness'''. Non sequitur ideas can be highly original and unusual, but are not as creative as ideas which are also appropriate to the situation. Tolkien's [[Lord of the Rings]] Trilogy is within the genre of fantasy writing, but has also shown itself to be both convincing and imaginative. |

||

| + | It is often useful to explicitly distinguish between ''creativity'' and ''innovation''. |

||

| − | ==Types of creativity and creatives== |

||

| − | In ''The Act of Creation'', [[Arthur Koestler]] ([[1964]] and various imprints) lists three types of creative individual — the ''Artist'', the ''Sage'' and the ''Jester''. Believers in this trinity hold all three elements necessary in [[business]] and can identify them in all in "truly creative" [[Company (law)| companies]] as well. |

||

| + | Creativity is typically used to refer to the act of producing new ideas, approaches or actions, while innovation is the process of both generating ''and applying'' such creative ideas in some specific context. |

||

| − | One can also categorise creativity by where and how it arises. |

||

| + | In the context of an organization, therefore, the term ''innovation'' is often used to refer to the entire process by which an organization generates creative new ideas and converts them into novel, useful and viable commercial products, services, and business practices, while the term ''creativity'' is reserved to apply specifically to the generation of novel ideas by individuals or groups, as a necessary step within the innovation process. |

||

| − | ==Measuring creativity== |

||

| − | [[Creativity]] of thousands Japanese which expressed in Problem Solving capability and Problem Recognizing capability has been measured in Japanese firms. Details:http://iccincsm.at.infoseek.co.jp. |

||

| + | For example, Amabile et al. (1996) suggest that while [[innovation]] "begins with creative ideas," |

||

| + | :"...creativity by individuals and teams ''is a starting point for innovation''; the first is a necessary ''but not sufficient'' condition for the second."<ref name='(Amabile et al., 1996 p. 1154-1155, emphasis added)'> {{cite journal | author=Amabile, T. M., R. Conti, H. Coon, et al. | year=1996 | title=Assessing the work environment for creativity | journal=Academy of Management Review | volume=39 | issue=5 | pages=1154–1184 | doi=10.2307/256995}}</ref> |

||

| + | Alternatively, there is no real difference between these terms, as creativity is both novel and appropriate (which implies successful application). It seems that creativity is preferred in art contexts whereas innovation in business ones. |

||

| − | The ultimate test of a creativity is history. Highly creative works will survive the passage of time to remain in our memories: [[Michelangelo]]'s Sistine Chapel, [[Isaac Newton]]'s Laws of Motion, [[Shakespeare]]'s plays. [[Genrich Altshuller]] introduced approaching creativity as an ''exact science'' with [[TRIZ]] in the [[1950s]]. The psychologist [[Robert Sternberg]] has proposed to apply the name ''[[creatology]]'' to scientific studies of creativity. |

||

| + | ==History of the term and the concept== |

||

| − | Creativity can be measured based on a response to a variety of test scenarios: |

||

| + | {{main|History of the concept of creativity}} |

||

| + | The ways in which societies have perceived the [[concept]] of creativity have changed throughout history, as has the term itself. The ancient Greek concept of [[art]] (in Greek, "''techne''"—the root of "technique" and "technology"), with the exception of [[poetry]], involved not freedom of action but subjection to ''rules''. In [[ancient Rome|Rome]], this Greek concept was partly shaken, and [[visual art]]ists were viewed as sharing, with poets, [[imagination]] and [[artistic inspiration]].<ref>[[Władysław Tatarkiewicz|Tatarkiewicz]], pp. 244–46.</ref> |

||

| − | * Expressing ideas: the ability to easily develop and juggle an abundance of associations and phrases when presented with a single word or image. |

||

| + | Although neither the Greeks nor the Romans had a word that directly corresponded to the word "creativity," their art, architecture, music, inventions and discoveries provide numerous examples of what today would be described as creative works. The Greek scientist of [[Syracuse]], [[Archimedes]] experienced the creative moment in his [[Eureka]] experience, finding the answer to a problem he had been wrestling with for a long time. At the time, the concept of "[[genius]]" probably came closest to describing the creative talents that brought forth such works.<ref name="Albert99">(Albert & Runco, 1999)</ref> |

||

| − | * Combining [[idea]]s in a new way: developing a wide range of innovative solutions when asked to explore new possibilities for an everyday item (such as a brick). |

||

| + | A fundamental change came in the [[Christianity|Christian]] period: "''creatio''" came to designate God's act of "creation from nothing". "''Creatio''" thus took on a different meaning than "''facere''" ("to make") and ceased to apply to human functions. The ancient view that art is not a domain of creativity persisted in this period.<ref name="Tatarkiewicz80">(Tatarkiewicz, 1980)</ref> |

||

| − | * Finding new uses for existing ideas: generating an original idea or solution based on a suggested existing idea |

||

| + | A shift occurred in modern times. [[Renaissance]] men had a sense of their own independence, freedom and creativity, and sought to give voice to this sense. The first to actually apply the word "creativity" was the Polish poet [[Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski]], who applied it exclusively to poetry. For over a century and a half, the idea of ''human'' creativity met with resistance, due to the fact that the term "creation" was reserved for creation "from nothing." [[Baltasar Gracián]] (1601–58) would only venture to write: "Art is the completion of nature, as if it were ''a second Creator''..."<ref>Tatarkiewicz, pp. 247–48.</ref> |

||

| − | * Expansion: the ability to work up a tentative idea into a practical solution. |

||

| + | By the 18th century and the [[Age of Enlightenment]], the concept of creativity was appearing more often in art theory, and was linked with the concept of [[imagination]].<ref name="Tatarkiewicz80"/> |

||

| − | * Focus and discrimination: recognizing the central challenge within an approach to a solution, while discounting any distracting minor elements, and then evaluating the difficulties. |

||

| + | The Western view of creativity can be contrasted with the Eastern view. For [[Hinduism|Hindus]], [[Confucianism|Confucianists]], [[Taoism|Taoists]] and [[Buddhism|Buddhists]], creation was at most a kind of discovery or mimicry, and the idea of creation "from nothing" had no place in these philosophies and religions.<ref name="Albert99"/> |

||

| − | * Perspective swapping: the ability to suggest ways of viewing a known problem from a completely different perspective. |

||

| + | In the West, by the 19th century, not only had art come to be regarded as creativity, but ''it alone'' was so regarded. When later, at the turn of the 20th century, there began to be discussion of creativity in the sciences (e.g., [[Jan Łukasiewicz]], 1878–1956) and in nature (e.g., [[Henri Bergson]]), this was generally taken as the transference, to the sciences, of concepts that were proper to art.<ref name="Tatarkiewicz80"/> |

||

| − | [[J. P. Guilford]]'s group constructed several tests to measure creativity: |

||

| + | In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, leading mathematicians and scientists such as [[Hermann von Helmholtz]] (1896) and [[Henri Poincaré]] (1908) began to reflect on and publicly discuss their creative processes, and these insights were built on in early accounts of the creative process by pioneering theorists such as [[Graham Wallas]] (1926) and [[Max Wertheimer]] (1945). |

||

| − | * Plot Titles where participants are given the plot of a story and asked to write original titles. |

||

| + | However, the formal starting point for the scientific study of creativity, from the standpoint of orthodox [[psychological]] literature, is generally considered to have been [[J. P. Guilford]]'s 1950 address to the [[American Psychological Association]], which helped popularize the topic<ref name="Sternberg99">(Sternberg, 1999)</ref> and focus attention on a scientific approach to conceptualizing creativity and measuring it [[psychometric]]ally. |

||

| − | * Quick Responses is a word association test scored for uncommonness. |

||

| + | In parallel with these developments, other investigators have taken a more pragmatic approach, teaching practical [[creativity techniques]]. Three of the best-known are: |

||

| − | * Figure Concepts where participants were given simple drawings of objects and individuals and asked to find qualities or features that are common by two or more drawings; these were scored for uncommonness. |

||

| + | * [[Alex Osborn]]'s "[[brainstorming]]" (1950s to present), |

||

| + | * [[Genrikh Altshuller]]'s Theory of Inventive Problem Solving ([[TRIZ]], 1950s to present), |

||

| + | * and [[Edward de Bono]]'s "[[lateral thinking]]" (1960s to present). |

||

| + | ==Creativity in psychology and cognitive science== |

||

| − | * Unusual Uses is finding unusual uses for common everyday objects such as bricks. |

||

| + | The study of the mental representations and processes underlying creative thought belongs to the domains of [[psychology]] and [[cognitive science]]. |

||

| + | A [[psychodynamic]] approach to understanding creativity was proposed by [[Sigmund Freud]], who suggested that creativity arises as a result of frustrated desires for fame, fortune, and love, with the energy that was previously tied up in frustration and emotional tension in the neurosis being sublimated into creative activity. Freud later retracted this view.{{Fact|date=June 2007}} |

||

| − | * Remote Associations where participants are asked to find a word between two given words (e.g. Hand _____ Call) |

||

| + | ====Graham Wallas==== |

||

| − | * Remote Consequences where participants are asked to generate a list of consequences of unexpected events (e.g. loss of gravity) |

||

| + | Graham Wallas & Richard Smith, in their work ''Art of Thought'', published in 1926, presented one of the first models of the creative process. In the Wallas stage model, creative insights and illuminations may be explained by a process consisting of 5 stages: |

||

| − | ==Social attitudes to creativity== |

||

| − | 'Creatitivity' is much praised in principle, but much derided in practice. Those in logical and ordered organisations may praise it but be reluctant to set a creative individual 'loose' in their ordered system. Business is increasingly claiming that [[profession]]al "creatives" do not have a monopoly on the concept of creativity, and that [[problem solving]] in general may require a flexible mind. Employers may value [[lawyer]]s, [[accountant]]s, people in [[sales]], and others more highly if such people can use a "creative" approach to their work, albeit within the confines of a logical and constraining system. The phrases "thinking outside the box" and "thinking outside the square" express this idea. |

||

| + | :(i) ''preparation'' (preparatory work on a problem that focuses the individual's mind on the problem and explores the problem's dimensions), |

||

| − | Ambivalence to creativity in the West may perhaps be due to the culture's image of creativity; the ingesting of [[Psychoactive drugs|drugs]] to generate [[Vision (religion)|visions]]; the celebration of [[eccentricity (behaviour)|eccentric]] behaviour; the possible cross-over between creativity and [[mental illness]]; the often [[bohemianism|bohemian]] sexual tastes of artists; the cultural association of artists with a life of poverty and misery. |

||

| + | :(ii) ''incubation'' (where the problem is internalized into the unconscious mind and nothing appears externally to be happening), |

||

| − | In the modern art context, the notion of creativity derives from [[Marxism]]. Under this system, the universe is meaningless and derived from [[randomness|random]] [[evolution]]. Creative art then, does not copy anything but is under the mastery of the artist. While this may make creativity the final refuge of freedom, it is [[nihilism|nihilistic]], meaningless, and not bound by standards or [[final cause]]s. |

||

| + | |||

| + | :(iii) ''intimation'' (the creative person gets a 'feeling' that a solution is on its way), |

||

| + | |||

| + | :(iv) ''illumination'' or insight (where the creative idea bursts forth from its [[preconscious]] processing into conscious awareness); and |

||

| + | |||

| + | :(v) ''verification'' (where the idea is consciously verified, elaborated, and then applied). |

||

| + | |||

| + | In numerous publications, Wallas' model is just treated as four stages, with "intimation" seen as a sub-stage. There has been some empirical research looking at whether, as the concept of "incubation" in Wallas' model implies, a period of interruption or rest from a problem may aid creative problem-solving. Ward<ref>(Ward, 2003)</ref> lists various hypotheses that have been advanced to explain why incubation may aid creative problem-solving, and notes how some empirical evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that incubation aids creative problem-solving in that it enables "forgetting" of misleading clues. Absence of incubation may lead the problem solver to become [[fixation|fixated]] on inappropriate strategies of solving the problem.<ref>(Smith, 1981)</ref> This work disputes the earlier hypothesis that creative solutions to problems arise mysteriously from the unconscious mind while the conscious mind is occupied on other tasks.<ref>(Anderson, 2000)</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | Wallas considered creativity to be a legacy of the [[evolution]]ary process, which allowed humans to quickly adapt to rapidly changing environments. Simonton<ref name="Simonton99">(Simonton, 1999)</ref> provides an updated perspective on this view in his book, ''Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity''. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ====J.P. Guilford==== |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[J. P. Guilford|Guilford]]<ref name="Guildford67">(Guilford, 1967)</ref> performed important work in the field of creativity, drawing a distinction between [[convergent and divergent production]] (commonly renamed convergent and divergent thinking). Convergent thinking involves aiming for a single, correct solution to a problem, whereas divergent thinking involves creative generation of multiple answers to a set problem. Divergent thinking is sometimes used as a synonym for creativity in psychology literature. Other researchers have occasionally used the terms ''flexible'' thinking or [[Fluid and crystallized intelligence|fluid intelligence]], which are roughly similar to (but not synonymous with) creativity. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ====Arthur Koestler==== |

||

| + | |||

| + | In ''The Act of Creation'', [[Arthur Koestler]]<ref name="Koestler64">(Koestler, 1964)</ref> lists three types of creative individual - the ''Artist'', the ''Sage'' and the ''Jester''. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Believers in this trinity hold all three elements necessary in [[business]] and can identify them all in "truly creative" [[Company (law)|companies]] as well. Koestler introduced the concept of ''bisociation'' - that creativity arises as a result of the intersection of two quite different frames of reference. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Geneplore model==== |

||

| + | In 1992 Finke et al. proposed the 'Geneplore' model, in which creativity takes place in two phases: a generative phase, where an individual constructs mental representations called preinventive structures, and an exploratory phase where those structures are used to come up with creative ideas. Weisberg<ref>(Weisberg, 1993)</ref> argued, by contrast, that creativity only involves ordinary cognitive processes yielding extraordinary results. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ====Conceptual blending==== |

||

| + | |||

| + | In the 90s, various approaches in cognitive science that dealt with [[metaphor]], [[analogy]] and [[structure mapping]] have been converging, and a new integrative approach to the study of creativity in science, art and humor has emerged under the label [[conceptual blending]]. |

||

| + | |||

| + | "''Creativity is the ability to illustrate what is outside the box from within the box''." '''-The Ride''' |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Psychological examples from science and mathematics== |

||

| + | ====Jacques Hadamard==== |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Jacques Hadamard]], in his book ''Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field'', uses [[introspection]] to describe mathematical thought processes. In contrast to authors who identify [[language]] and [[cognition]], he describes his own mathematical thinking as largely wordless, often accompanied by [[mental images]] that represent the entire solution to a problem. He surveyed 100 of the leading physicists of his day (ca. 1900), asking them how they did their work. Many of the responses mirrored his own. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Hadamard described the experiences of the [[mathematician]]s/[[theoretical physicist]]s [[Carl Friedrich Gauss]], [[Hermann von Helmholtz]], [[Henri Poincaré]] and others as viewing entire solutions with “sudden spontaneity.”<ref> Hadamard, 1954, pp. 13-16.</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | The same has been reported in literature by many others, such as Denis Brian,<ref> Brian, 1996, p. 159.</ref> [[G. H. Hardy]]<ref>G. H. Hardy cited how the mathematician [[Srinivasa Ramanujan]] had “moments of sudden illumination.” See Kanigel, 1992, pp. 285-286.</ref> [[Walter Heitler]],<ref>Interview with Walter Heitler by John Heilbron (March 18, 1963. Archives for the History of Quantum Physics), as cited in and quoted from in Gavroglu, Kostas ''[[Fritz London]]: A Scientific Biography'' p. 45 (Cambridge, 2005).</ref> [[B. L. van der Waerden]],<ref>von Franz, 1992, p. 297 and 314. Cited work: B. L. van der Waerden, ''Einfall und Überlegung: Drei kleine Beiträge zur Psychologie des mathematischen Denkens'' (Gasel & Stuttgart, 1954).</ref> and Harold Ruegg.<ref>von Franz, 1992, p. 297 and 314. Cited work: Harold Ruegg, ''Imagination: An Inquiry into the Sources and Conditions That Stimulate Creativity'' (New York: Harper, 1954).</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | To elaborate on one example, [[Albert Einstein|Einstein]], after years of fruitless calculations, suddenly had the solution to the general theory of relativity revealed in a dream “like a giant die making an indelible impress, a huge map of the universe outlined itself in one clear vision.”<ref> Brian, 1996, p. 159.</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | Hadamard described the process as having steps (i) preparation, (ii) incubation, (iv) illumination, and (v) verification of the five-step [[Graham Wallas]] creative-process model, leaving out (iii) intimation, with the first three cited by Hadamard as also having been put forth by Helmholtz:<ref> Hadamard, 1954, p. 56.</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | ====Marie-Louise von Franz==== |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Marie-Louise von Franz]], a colleague of the eminent psychiatrist [[Carl Jung]], noted that in these unconscious scientific discoveries the “always recurring and important factor ... is the simultaneity with which the complete solution is intuitively perceived and which can be checked later by discursive reasoning.” She attributes the solution presented “as an [[archetypal]] pattern or image.”<ref> von Franz, 1992, pp. 297-298.</ref> As cited by von Franz,<ref>von Franz, 1992 297-298 and 314.</ref> according to Jung, “Archetypes ... manifest themselves only through their ability to ''organize'' images and ideas, and this is always an unconscious process which cannot be detected until afterwards.”<ref>Jung, 1981, paragraph 440, p. 231.</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Creativity and affect== |

||

| + | |||

| + | Some theories suggest that creativity may be particularly susceptible to affective influence. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Creativity and positive affect relations=== |

||

| + | According to Isen, positive affect has three primary effects on cognitive activity: |

||

| + | |||

| + | #Positive affect makes additional cognitive material available for processing, increasing the number of cognitive elements available for association; |

||

| + | #Positive affect leads to defocused attention and a more complex cognitive context, increasing the breadth of those elements that are treated as relevant to the problem; |

||

| + | #Positive affect increases cognitive flexibility, increasing the probability that diverse cognitive elements will in fact become associated. Together, these processes lead positive affect to have a positive influence on creativity. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Fredrickson in her [[Broaden and Build Model]] suggests that positive emotions such as joy and love broaden a person’s available repertoire of cognitions and actions, thus enhancing creativity. |

||

| + | |||

| + | According to these researchers, positive emotions increasing the number of cognitive elements available for association (attention scope) and the number of elements that are relevant to the problem (cognitive scope). |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Creativity and negative affect relations=== |

||

| + | |||

| + | On the other hand, some theorists have suggested that negative affect leads to greater creativity. A cornerstone of this perspective is empirical evidence of a relationship between affective illness and creativity. In a study of 1,005 prominent 20th century individuals from over 45 different professions, the University of Kentucky’s Arnold Ludwig found a slight but significant correlation between depression and level of creative achievement. In addition, several systematic studies of highly - creative individuals and their relatives have uncovered a higher incidence of affective disorders (primarily bipolar illness and depression) than that found in the general population. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Creativity and affect at work=== |

||

| + | Three patterns may exist between affect and creativity at work: positive (or negative) mood, or change in mood, predictably precedes creativity; creativity predictably precedes mood; and whether affect and creativity occur simultaneously. |

||

| + | It was found that not only might affect precede creativity, but creative outcomes might provoke affect as well. At its simplest level, the experience of creativity is itself a work event, and like other events in the organizational context, it could evoke emotion. Qualitative research and anecdotal accounts of creative achievement in the arts and sciences suggest that creative insight is often followed by feelings of elation. For example, Albert Einstein called his 1907 general theory of relativity “the happiest thought of my life.” Empirical evidence on this matter is still very tentative, |

||

| + | In contrast to the possible [[Incubation (psychology)|incubation]] effects of affective state on subsequent creativity, the affective consequences of creativity are likely to be more direct and immediate. In general, affective events provoke immediate and relatively-fleeting emotional reactions. Thus, if creative performance at work is an affective event for the individual doing the creative work, such an effect would likely be evident only in same-day data. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Another longitudinal research found several insights regarding the relations between creativity and emotion at work. First - a positive relationship between positive affect and creativity, and no evidence of a negative relationship. The more positive a person’s affect on a given day, the more creative thinking they evidenced that day and the next day – even controlling for that next day’s mood. There was even some evidence of an effect two days later |

||

| + | |||

| + | In addition, the researchers found no evidence that people were more creative when they experienced both positive and negative affect on the same day. The weight of evidence supports a purely linear form of the affect-creativity relationship, at least over the range of affect and creativity covered in our study: the more positive a person’s affect, the higher their creativity in a work setting. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, they found four patterns of affect and creativity affect can operate as an antecedent to creativity; as a direct consequence of creativity; as an indirect consequence of creativity; and affect can occur simultaneously with creative activity. Thus, it appears that people’s feelings and creative cognitions are interwoven in several distinct ways within the complex fabric of their daily work lives. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Creativity and intelligence== |

||

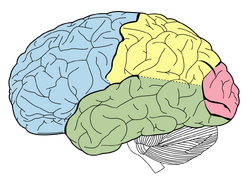

| + | {{Cerebrum map|Cerebral Cortex|caption=The [[frontal lobe]] (shown in blue) is thought to play an important role in creativity}} |

||

| + | There has been debate in the psychological literature about whether [[intelligence]] and creativity are part of the same process (the conjoint hypothesis) or represent distinct mental processes (the disjoint hypothesis). Evidence from attempts to look at correlations between intelligence and creativity from the 1950s onwards, by authors such as Barron, Guilford or Wallach and Kogan, regularly suggested that correlations between these concepts were low enough to justify treating them as distinct concepts. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Some researchers believe that creativity is the outcome of the same cognitive processes as intelligence, and is only judged as creativity in terms of its consequences, i.e. when the outcome of cognitive processes happens to produce something novel, a view which Perkins has termed the "nothing special" hypothesis.<ref name="OHara99">(O'Hara & Sternberg, 1999)</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | A very popular model is what has come to be known as "the threshold hypothesis", proposed by [[Ellis Paul Torrance]], which holds that a high degree of intelligence appears to be a [[necessary and sufficient conditions|necessary but not sufficient condition]] for high creativity.<ref name="Guildford67"/> This means that, in a general sample, there will be a positive [[correlation]] between creativity and intelligence, but this correlation will not be found if only a sample of the most highly intelligent people are assessed. Research into the threshold hypothesis, however, has produced mixed results ranging from enthusiastic support to refutation and rejection.<ref>(Plucker & Renzulli, 1999)</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | An alternative perspective, Renzulli's three-rings hypothesis, sees giftedness as based on both intelligence and creativity. More on both the threshold hypothesis and Renzulli's work can be found in O'Hara and Sternberg.<ref name="OHara99"/> |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Neurobiology of creativity== |

||

| + | The [[neurobiology]] of creativity has been addressed<ref name="NeuroPsychiatry">(Kenneth M Heilman, MD, Stephen E. Nadeau, MD, and David Q. Beversdorf, MD. "Creative Innovation: Possible Brain Mechanisms" Neurocase (2003)</ref> in the article "Creative Innovation: Possible Brain Mechanisms." The authors write that "creative innovation might require coactivation and communication between regions of the brain that ordinarily are not strongly connected". Highly creative people who excel at creative innovation tend to differ from others in three ways: |

||

| + | * they have a high level of specialized knowledge, |

||

| + | *they are capable of [[convergent and divergent production|divergent thinking]] mediated by the [[frontal lobe]], |

||

| + | *and they are able to modulate [[neurotransmitters]] such as [[norepinephrine]] in their frontal lobe. |

||

| + | Thus, the frontal lobe appears to be the part of the [[Cerebral cortex|cortex]] that is most important for creativity. |

||

| + | |||

| + | This article also explored the links between creativity and sleep, [[Mood disorder|mood]] and [[Addiction|addiction disorders]], and [[Depression (mood)|depression]]. |

||

| + | |||

| + | In 2005, Alice Flaherty presented a three-factor model of the creative drive. Drawing from evidence in brain imaging, drug studies and lesion analysis, she described the creative drive as resulting from an interaction of the frontal lobes, the [[temporal lobe]]s, and [[dopamine]] from the [[limbic system]]. The frontal lobes can be seen as responsible for idea generation, and the temporal lobes for idea editing and evaluation. Abnormalities in the frontal lobe (such as depression or anxiety) generally decrease creativity, while abnormalities in the temporal lobe often increase creativity. High activity in the temporal lobe typically inhibits activity in the frontal lobe, and vice versa. High dopamine levels increase general [[arousal]] and goal directed behaviors and reduce [[latent inhibition]], and all three effects increase the drive to generate ideas.<ref>(Flaherty, 2005)</ref> |

||

| + | ===Working memory and the cerebellum=== |

||

| + | Vandervert<ref>Vandervert 2003a, 2003b; Vandervert, Schimpf & Liu, 2007</ref> described how the brain’s frontal lobes and the cognitive functions of the cerebellum collaborate to produce creativity and innovation. Vandervert’s explanation rests on considerable evidence that all processes of working memory (responsible for processing all thought<ref>Miyake & Shah, 1999</ref>) are adaptively modeled by the cerebellum.<ref>Schmahmann, 1997, 2004</ref> The cerebellum (consisting of 100 billion neurons, which is more than the entirety of the rest of the brain<ref>Andersen, Korbo & Pakkenberg, 1992</ref> is also widely known to adaptively model all bodily movement. The cerebellum’s adaptive models of working memory processing are then fed back to especially frontal lobe working memory control processes<ref>Miller & Cohen, 2001</ref> where creative and innovative thoughts arise.<ref>Vandervert, 2003a</ref> (Apparently, creative insight or the ‘’aha’’ experience is then triggered in the temporal lobe.<ref>Jung-Beeman, Bowden, Haberman, Frymiare, Arambel-Liu, Greenblatt, Reber & Kounios, 2004</ref>) According to Vandervert, the details of creative adaptation begin in ‘’forward’’ cerebellar models which are anticipatory/exploratory controls for movement and thought. These cerebellar processing and control architectures have been termed Hierarchical Modular Selection and Identification for Control (HMOSAIC).<ref>Imamizu, Kuroda, Miyauchi, Yoshioka & Kawato, 2003</ref> New, hierarchically arranged levels of the cerebellar control architecture (HMOSAIC) develop as mental mulling in working memory is extended over time. These new levels of the control architecture are fed forward to the frontal lobes. Since the cerebellum adaptively models all movement and all levels of thought and emotion,<ref>Schmahmann, 2004,</ref> Vandervert’s approach helps explain creativity and innovation in sports, art, music, the design of video games, technology, mathematics and thought in general. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Creativity and mental health== |

||

| + | {{main|Creativity and mental illness}} |

||

| + | |||

| + | A study by psychologist [[J. Philippe Rushton]] found creativity to correlate with [[intelligence (trait)|intelligence]] and [[psychoticism]].<ref>(Rushton, 1990)</ref> Another study found creativity to be greater in [[schizotypal]] than in either normal or [[schizophrenia|schizophrenic]] individuals. While divergent thinking was associated with bilateral activation of the [[prefrontal cortex]], schizotypal individuals were found to have much greater activation of their ''right'' prefrontal cortex.<ref>http://exploration.vanderbilt.edu/news/news_schizotypes.htm ([http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.06.016 Actual paper])</ref> This study hypothesizes that such individuals are better at accessing both hemispheres, allowing them to make novel associations at a faster rate. In agreement with this hypothesis, [[ambidexterity]] is also associated with [[schizotypal]] and [[schizophrenia|schizophrenic]] individuals. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Particularly strong links have been identified between creativity and [[mood disorder]]s, particularly [[manic-depressive disorder]] (a.k.a. [[bipolar disorder]]) and [[depressive disorder]] (a.k.a. [[unipolar disorder]]). In ''Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament'', [[Kay Redfield Jamison]] summarizes studies of mood-disorder rates in '''[[writers]]''', '''[[poets]]''' and '''[[artists]]'''. She also explores research that identifies [[mood disorder]]s in such famous writers and artists as [[Ernest Hemingway]] (who shot himself after [[electroconvulsive treatment]]), [[Virginia Woolf]] (who drowned herself when she felt a depressive episode coming on), composer [[Robert Schumann]] (who died in a mental institution), and even the famed [[visual artist]] [[Michelangelo]]. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Creativity in various contexts== |

||

| + | Creativity has been studied from a variety of perspectives and is important in numerous contexts. Most of these approaches are undisciplinary, and it is therefore difficult to form a coherent overall view.<ref name="Sternberg99"/> The following sections examine some of the areas in which creativity is seen as being important. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Creativity in diverse cultures=== |

||

| + | |||

| + | Creativity is a scientific concept which is mostly rooted within a Western creationist perspective. Francois Jullien in 'Process and Creation, 1989' is inviting us to look at that concept from a Chinese cultural point of view. Fangqi Xu<ref>[http://www.cct.umb.edu/fangqi.pdf Fangqi Xu, et. al. ''A Survey of Creativity Courses at Universities in Principal Countries'']</ref> has reported creativity courses in a range of countries. Todd Lubart has studied extensively the cultural aspects of creativity and innovation. |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:HenryMoore RecliningFigure 1951.jpg|thumb|300px|left|[[Henry Moore]]'s ''Reclining Figure'']] |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Creativity in art and literature=== |

||

| + | Most people associate creativity with the fields of [[art]] and [[literature]]. In these fields, ''originality'' is considered to be a sufficient condition for creativity, unlike other fields where both ''originality'' and ''appropriateness'' are necessary.<ref name="Amabile98">(Amabile, 1998; Sullivan and Harper, 2009)</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | Within the different modes of artistic expression, one can postulate a continuum extending from "[[interpretation (logic)|interpretation]]" to "innovation". Established [[art movements|artistic movement]]s and [[genre]]s pull practitioners to the "interpretation" end of the scale, whereas original thinkers strive towards the "innovation" pole. Note that we conventionally expect some "creative" people (dancers, actors, orchestral members, etc.) to perform (interpret) while allowing others (writers, painters, composers, etc.) more freedom to express the new and the different. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Contrast alternative theories, for example: |

||

| + | * artistic [[inspiration]], which provides the transmission of [[Vision (religion)|vision]]s from divine sources such as the [[Muse (band)|Muse]]s; a taste of the Divine. Compare with [[invention]]. |

||

| + | * artistic [[evolution]], which stresses obeying established ("classical") rules and imitating or [[appropriation (art)|appropriating]] to produce subtly different but unshockingly understandable work. Compare with [[crafts]]. |

||

| + | * artistic conversation, as in [[Urrealism]], which stresses the depth of communication when the creative product is the language. |

||

| + | |||

| + | In the [[art]], practice and [[theory]] of [[Davor Dzalto]], human creativity is taken as a basic feature of both the personal [[existence]] of [[human being]] and [[art]] production. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Creative industries and services=== |

||

| + | Today, creativity forms the core activity of a growing section of the [[global economy]] — the so-called "[[creative industries]]" — capitalistically generating (generally non-tangible) [[wealth]] through the creation and [[exploitation]] of [[intellectual property]] or through the provision of [[creative services]]. The [http://www.culture.gov.uk/global/publications/archive_2001/ci_mapping_doc_2001.htm Creative Industries Mapping Document 2001] provides an overview of the creative industries in the UK. The [[creative professional]] workforce is becoming a more integral part of industrialized nations' economies. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Creative professions include writing, art, design, theater, television, radio, motion pictures, related crafts, as well as marketing, strategy, some aspects of scientific research and development, product development, some types of teaching and curriculum design, and more. Since many creative professionals (actors and writers, for example) are also employed in secondary professions, estimates of creative professionals are often inaccurate. By some estimates, approximately 10 million US workers are creative professionals; depending upon the depth and breadth of the definition, this estimate may be double. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Creativity in other professions=== |

||

| + | [[Image:NewtonsPrincipia.jpg|thumb|180px|right|[[Isaac Newton]]'s law of gravity is popularly attributed to a ''creative leap'' he experienced when observing a falling apple.]] |

||

| + | Creativity is also seen as being increasingly important in a variety of other professions. [[Architecture]] and [[industrial design]] are the fields most often associated with creativity, and more generally the fields of [[design]] and [[design research]]. These fields explicitly value creativity, and journals such as ''Design Studies'' have published many studies on creativity and creative problem solving.<ref>for a typical example see (Dorst et al., 2001)</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | Fields such as [[science]] and [[engineering]] have, by contrast, experienced a less explicit (but arguably no less important) relation to creativity. Simonton<ref name="Simonton99"/> shows how some of the major scientific advances of the 20th century can be attributed to the creativity of individuals. This ability will also be seen as increasingly important for engineers in years to come.<ref>(National Academy of Engineering 2005)</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | Accounting has also been associated with creativity with the popular euphemism ''[[creative accounting]]''. Although this term often implies unethical practices, Amabile<ref name="Amabile98"/> has suggested that even this profession can benefit from the (ethical) application of creative thinking. Al-Beraidi and Rickards had demonstrated that to be the case in a study of Saudi Arabian financial consultants and accounting professionals<ref>Al-Beraidi, M., and Rickards, T., (2006). "Rethinking Creativity in the Accounting Profession: to be professional and creative", Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, Vol 2,1, 25-41</ref> |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Creativity in organizations=== |

||

| + | Amabile<ref name="Amabile98"/> argued that to enhance creativity in business, three components were needed: |

||

| + | * Expertise (technical, procedural & intellectual knowledge), |

||

| + | * Creative thinking skills (how flexibly and imaginatively people approach problems), |

||

| + | *and Motivation (especially [[intrinsic motivation]]). |

||

| + | |||

| + | In 1986 in Europe, The Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research, [[TNO]], supported an international conference [http://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&id=bg0jw7d5hXcC&dq=Creativity+Innovation+towards+European+Network&printsec=frontcover&source=web&ots=gh5PcHZzRr&sig=BGJnO4w6oeTwkT43WzHxve-i3ac&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result Creativity and Innovation: towards a European Network] with the intention of helping ‘build a greater understanding of innovation and creative processes’ across Europe. |

||

| + | |||

| + | The organizing committee became known as the Periscope group which also helped in the formation of a sister organization in America coordinated by the Prism group. Stan Gryskiewicz of The Center for Creative Leadership and a member of the Prism group reported in 1992 that </blockquote> |

||

| + | The conference was to be the first in a series of events still held biennially in Europe. In alternative years a similar sequence of conferences have been held in North American venues, with collaboration between the steering groups.<ref> Gryskiewicz, S., (1992) Letter from America (With respectful acknowledgement to Alistair Cooke), Creativity and Innovation Management, 1,4, 214-215</ref> |

||

| + | </blockquote> |

||

| + | |||

| + | Nonaka, who examined several successful Japanese companies, similarly saw creativity and knowledge creation as being important to the success of organizations.<ref name="Nonaka91">(Nonaka, 1991)</ref> In particular, he emphasized the role that [[tacit knowledge]] has to play in the creative process. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ===Economic views of creativity=== |

||

| + | |||

| + | In the early 20th century, [[Joseph Schumpeter]] introduced the economic theory of ''[[creative destruction]]'', to describe the way in which old ways of doing things are endogenously destroyed and replaced by the new. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Creativity is also seen by economists such as [[Paul Romer]] as an important element in the recombination of elements to produce new technologies and products and, consequently, economic growth. Creativity leads to [[Capital (economics)|capital]], and creative products are protected by [[intellectual property]] laws. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Creativity is also an important aspect to understanding [[Entrepreneurship]]. |

||

| + | |||

| + | The ''[[creative class]]'' is seen by some to be an important driver of modern economies. In his 2002 book, ''The Rise of the Creative Class'', [[economist]] [[Richard Florida]] popularized the notion that regions with "3 T's of economic development: Technology, Talent and Tolerance" also have high concentrations of [[creative professional]]s and tend to have a higher level of economic development. |

||

==Fostering creativity== |

==Fostering creativity== |

||

| + | {{main|creativity techniques}} |

||

| − | Some see the conventional system of [[education | schooling]] as "stifling" of creativity and attempt (particularly in the [[pre-school]]/[[kindergarten]] and early school years) to provide a creativity-friendly, rich, imagination-fostering environment for young children. Compare [[Waldorf School]]. |

||

| + | {{Main|The teaching of creativity}} |

||

| + | Daniel Pink, in his 2005 book ''A Whole New Mind'', repeating arguments posed throughout the 20th century, argues that we are entering a new age where creativity is becoming increasingly important. In this ''conceptual age'', we will need to foster and encourage ''right-directed thinking'' (representing creativity and emotion) over ''left-directed thinking'' (representing logical, analytical thought). |

||

| − | A growing number of pop psychologists are making money off the idea that one can learn to become more "creative". Several different researchers have proposed several different approaches to prop up this idea, ranging from [[psychology| psychological]]-cognitive, such as: |

||

| + | Nickerson<ref>(Nickerson, 1999)</ref> provides a summary of the various creativity techniques that have been proposed. These include approaches that have been developed by both academia and industry: |

||

| − | * [[Synectics]] |

||

| + | # Establishing purpose and intention |

||

| − | * Purdue Creative Thinking Program |

||

| + | # Building basic skills |

||

| − | * [[lateral thinking]] (courtesy of [[Edward de Bono]]) |

||

| + | # Encouraging acquisitions of domain-specific knowledge |

||

| − | to the highly structured such as: |

||

| + | # Stimulating and rewarding curiosity and exploration |

||

| − | * [[TRIZ]], the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving |

||

| + | # Building motivation, especially internal motivation |

||

| − | * [[ARIZ]], the [[Algorithm of Inventive Problems Solving | Algorithm of Inventive Problem-Solving]] both developed by the Russian scientist [[Genrich Altshuller]]. |

||

| + | # Encouraging confidence and a willingness to take risks |

||

| − | * Computer-Aided [[Morphological analysis]]. Presented at [http://www.swemorph.com Swedish Morphological Society]. |

||

| + | # Focusing on mastery and self-competition |

||

| + | # Promoting supportable beliefs about creativity |

||

| + | # Providing opportunities for choice and discovery |

||

| + | # Developing self-management (metacognitive skills) |

||

| + | # Teaching techniques and strategies for facilitating creative performance |

||

| + | # Providing balance |

||

| − | See also: [[creativity techniques]]. |

||

| + | ==Enhancing the creative process with new technologies== |

||

| − | A study by the psychologist [[J. Philippe Rushton]] found that creativity correlated with [[intelligence (trait)|intelligence]] and [[psychoticism]] (Rushton, 1990). |

||

| + | |||

| + | A simple but accurate [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WGR-4G65VJ1-1&_user=10&_coverDate=10%2F31%2F2005&_alid=527112635&_rdoc=1&_fmt=summary&_orig=search&_cdi=6829&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=3ad4369ed718542426a8f4ace61c7d8f review] on this new Human-Computer Interactions (HCI) angle for promoting creativity has been written by Todd Lubart, an invitation full of creative ideas to develop further this new field. |

||

| + | |||

| + | The Creativity and Cognition conference series, sponsored by the ACM and running since 1993 has been an important venue for publishing research on the intersection between technology and creativity. The conference now runs biannually, next taking place in 2009. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Social attitudes to creativity== |

||

| + | Although the benefits of creativity to society as a whole have been noted,<ref>(Runco 2004)</ref> social attitudes about this topic remain divided. The wealth of literature regarding the development of creativity<ref>see (Feldman, 1999) for example</ref> and the profusion of [[creativity techniques]] indicate wide acceptance, at least among academics, that creativity is desirable. |

||

| + | |||

| + | There is, however, a dark side to creativity, in that it represents a ''"quest for a radical autonomy apart from the constraints of social responsibility"''.<ref>(McLaren, 1999)</ref> In other words, by encouraging creativity we are encouraging a departure from society's existing norms and values. Expectation of conformity runs contrary to the spirit of creativity. Nevertheless, employers are increasingly valuing creative skills. A report by the Business Council of Australia, for example, has called for a higher level of creativity in graduates.<ref>(BCA, 2006)</ref> The ability to "[[think outside the box]]" is highly sought after. However, the above-mentioned paradox may well imply that firms pay lip service to thinking outside the box while maintaining traditional, hierarchical organization structures in which individual creativity is not rewarded. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Creativity Journals== |

||

| + | |||

| + | Journals specialising in articles on creativity include: [[Creativity Research Journal]], [[Creativity and Innovation Management]], and [[The Journal of Creative Behavior]]. |

||

| − | ==Periods and Personalities== |

||

| − | ; Ancient Greece |

||

| − | *[[Plato]]'s [[Ion (dialogue)|Dialogue of Ion]] |

||

| − | ; [[4th century]] of the Christian Era |

||

| − | *[[Pappus of Alexandria]] introduced the term "[[heuristics]]" |

||

| − | ;[[1470s]] |

||

| − | *[[Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

| − | ; Early [[20th century]] |

||

| − | *[[Pablo Picasso]] painter |

||

| − | *[[Marcel Duchamp]] artist |

||

| − | ;[[1940s]] |

||

| − | *[[Fritz Zwicky]] - [[Morphological Analysis]] |

||

| − | *[[Lawrence Delos Miles]] |

||

| − | *[[George Polya]] |

||

| − | ;[[1950s]] |

||

| − | *[[Alex Osborn]] |

||

| − | *[[Sid Parnes]] |

||

| − | ;[[1950s]] |

||

| − | *[[Genrich Altshuller | Genrikh Altshuller]] - [[TRIZ]], [[ARIZ]] |

||

| − | ;[[1960s]] |

||

| − | *[[Carl Jung]] classified creativity as one of the five main instinctive forces in humans (Jung 1964) |

||

| − | *[[Edward Matchett]] - [[Fundamental design method]] (1968) |

||

| − | * [[Carl Rogers]]'s essay "Towards a Theory of Creativity" (1961): |

||

| − | *[[Wiliam Gordon]] - [[Synectics]] |

||

| − | *[[Edward de Bono]] - [[Lateral thinking]] |

||

| − | ;[[1970s]] |

||

| − | *[[Albert Rothenberg]] coined the term '[[Janusian thinking]]' |

||

| − | *[[Yoji Akao]] - [[Quality function deployment]] |

||

| − | *[[Total creativity]] - the ultimate goal in the philosophy of [[John David Garcia]] |

||

| − | *[[Carlos Castaneda]] - A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with Don Juan |

||

| − | ;[[1980s]] |

||

| − | *[[Paul Palnik]]- [[Creative Consciousness]] The healthiest state of mind. [1981] |

||

| − | *[[Robert Sternberg]] proposed the name "[[creatology]]" |

||

| − | ;[[1990s]] |

||

| − | *Idan Gafni - association expansion cards concept ([[Object Pairing]]) |

||

| − | *Tom Ritchey - Computer-Aided [[Morphological analysis]] |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| − | *[[ |

+ | *[[Ability]] |

| − | *[[ |

+ | *[[Archetecture]] |

| + | *[[Artistic ability]] |

||

| + | *[[Arts]] |

||

*[[Creative writing]] |

*[[Creative writing]] |

||

| − | *[[Creativity |

+ | *[[Creativity and mental illness]] |

| − | *[[ |

+ | *[[Divergent thinking]] |

| + | *[[Gifted]] |

||

| − | *[[Flow (psychology)|Flow]] |

||

| − | *[[Intelligence |

+ | *[[Intelligence]] |

| + | *[[Mathematical ability]] |

||

| − | *[[Innovation]] |

||

| − | *[[ |

+ | *[[Musical ability]] |

| + | *[[Openness to experience]] |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== |

||

| + | {{reflist|2}} |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Albert, R.S. & Runce, M.A. | chapter=A History of Research on Creativity | editor=ed. Sternberg, R.J. | title=Handbook of Creativity | year=1999 | publisher=Cambridge University Press}} |

||

| − | * [[Stevan Harnad]]. (1982) [http://cogprints.org/1569/ Metaphor and Mental Duality] in Simon, T. and Scholes, R., Eds. ''Language, mind and brain''. Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum pp. 189-211. [http://cogprints.org/1627/ Creativity: Method or Magic?] |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Amabile, T.M. | year=1998 | title=How to kill creativity | journal=[[Harvard Business Review]] | volume=76 | issue=5}} |

||

| − | * {{Journal reference | Author=Rushton, J.P. | Title=Creativity, intelligence, and psychoticism | Journal=Personality and Individual Differences | Year=1990 | Volume=11 | |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Amabile, T.M. | year=1996 | title=Creativity in context | publisher=Westview Press}} |

||

| − | Pages=1291–1298}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Anderson, J.R. | year=2000 | title=Cognitive psychology and its implications | publisher=Worth Publishers}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Alvino, Carlos Eduardo Paladino, Silvia Regina Winetzki, Jethro de LoxLok, Verônica de Thule M.A. | editor=ed. Núcleo de Inteligência | title=[http://adorina.blogspot.com/ Tratado de Alquimia]| year=2007 | publisher=Núcleo de Inteligência}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Ayan,Jordan | year=1997 | title=Aha! - 10 Ways To Free Your Creative Spirit and Find Your Great Ideas | publisher=Random House}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Balzac, Fred | year=2006 | title=[http://www.neuropsychiatryreviews.com/may06/einstein.html Exploring the Brain's Role in Creativity] | journal=NeuroPsychiatry Reviews | volume=7 | issue=5 | pages=pp. 1, 19-20}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=BCA | year=2006 | title=New Concepts in Innovation: The Keys to a Growing Australia | publisher=[http://www.bca.com.au Business Council of Australia]}} |

||

| + | * Brian, Denis, ''Einstein: A Life'' (John Wiley and Sons, 1996) ISBN 0-471-11459-6 |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Boden, M.A. | year=2004 | title=The Creative Mind: Myths And Mechanisms | publisher=Routledge | authorlink=Margaret Boden}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Carson, S.H. | coauthors=Peterson, J.B., Higgins, D.M. | year=2005 | title=Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure of the Creative Achievement Questionnaire | journal=Creativity Research Journal | volume=17 | issue=1 | pages=37-50}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Craft, A. | year=2005 | title=Creativity in Schools: tensions and dilemmas | publisher=Routledge | authorlink=Anna Craft}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Dorst, K. | coauthors=Cross, N. | year=2001 | title=Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution | journal=Design Studies | volume=22 | issue=5 | pages=425-437}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Feldman, D.H. | chapter=The Development of Creativity | editor=ed. Sternberg, R.J. | title=Handbook of Creativity | year=1999 | publisher=Cambridge University Press}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Finke, R. | coauthors=Ward, T.B. & Smith, S.M. | year=1992 | title=Creative cognition: Theory, research, and applications | publisher=MIT Press}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author= Flaherty, A.W, | year = 2005 | journal = Journal of Comparative Neurology | title = Frontotemporal and dopaminergic control of idea generation and creative drive | volume = 493 | issue = 1 | pages = 147-153 | pmid = 16254989}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Florida, R. | year=2002 | title=The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It's Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life | publisher=Basic Books | authorlink=Richard Florida}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Guilford, J.P. | year=1967 | title=The Nature of Human Intelligence | authorlink=J. P. Guilford}} |

||

| + | * [[Jacques Hadamard|Hadamard, Jacques]], ''The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field'' (Dover, 1954) ISBN 0-486-20107-4 |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Helmholtz, H. v. L. | title=Vortrage und reden (5th Auffl.) | year=1896 | publisher=Friederich Vieweg und Sohn}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author= Jeffery. G. | title= The Creative College: building a successful learning culture in the arts | year=2005 | publisher=Trentham Books | authorlink= Graham Jeffery}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Johnson, D.M. | title=Systematic introduction to the psychology of thinking | year=1972 | publisher=Harper & Row}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Jullien, F.; Paula M. Varsano (Translator) | title=In Praise of Blandness: Proceeding from Chinese Thought and Aesthetics | year=2004 | publisher=Zone Books,U.S.}} ISBN-10: 1890951412; ISBN-13: 978-1890951412 |

||

| + | * [[Carl Jung|Jung, C. G.]], ''The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Volume 8. The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. '' (Princeton, 1981) ISBN 0-691-09774-7 |

||

| + | *Kanigel, Robert, ''The Man Who Knew Infinity: A Life of the Genius Ramanujan '' (Washington Square Press, 1992) ISBN 0-671-75061-5 |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Kraft, U. | title=Unleashing Creativity | journal=[[Scientific American Mind]] | year=2005 | volume=April | pages=16-23}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Koestler, A. | title=The Act of Creation | year=1964 | authorlink=Arthur Koestler}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=McLaren, R.B. | chapter=Dark Side of Creativity | editor=ed. Runco, M.A. & Pritzker, S.R. | title=Encyclopedia of Creativity | year=1999 | publisher=Academic Press}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=McCrae, R.R. | title=Creativity, Divergent Thinking, and Openness to Experience | journal=Journal of Personality and Social Psychology | year=1987 | volume=52 | issue=6 | pages=1258-1265}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Michalko, M. | title=Cracking Creativity: The Secrets of Creative Genius }} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Nachmanovitch, Stephen | year=1990 | title=Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art | publisher=Penguin-Putnam}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=National Academy of Engineering | year=2005 | title=Educating the engineer of 2020 : adapting engineering education to the new century | publisher=National Academies Press | authorlink=National Academy of Engineering}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Nickerson, R.S. | chapter=Enhancing Creativity | editor=ed. Sternberg, R.J. | title=Handbook of Creativity | year=1999 | publisher=Cambridge University Press}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Nonaka, I. | year=1991 | title=The Knowledge-Creating Company | journal=Harvard Business Review | volume=69 | issue=6 | pages=96-104}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=O'Hara, L.A. & Sternberg, R.J. | chapter=Creativity and Intelligence | editor=ed. Sternberg, R.J. | title=Handbook of Creativity | year=1999 | publisher=Cambridge University Press}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Pink, D.H. | year=2005 | title=A Whole New Mind: Moving from the information age into the conceptual age | publisher=Allen & Unwin}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Plucker, J.A. & Renzulli, J.S. | chapter=Psychometric Approaches to the Study of Human Creativity | editor=ed. Sternberg, R.J. | title=Handbook of Creativity | year=1999 | publisher=Cambridge University Press}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Poincaré, H. | chapter=Mathematical creation | editor=ed. Ghiselin, B. | title=The Creative Process: A Symposium | year=1908/1952 | publisher=Mentor}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Rhodes, M. | year=1961 | title=An analysis of creativity | journal=Phi Delta Kappan | volume=42 | pages=305-311}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Rushton, J.P. | title=Creativity, intelligence, and psychoticism | journal=Personality and Individual Differences | year=1990 | volume=11 | pages=1291-1298 | authorlink=J. Philippe Rushton}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Runco, M.A. | year=2004 | title=Creativity | journal=Annual Review of Psychology | volume=55 | pages=657-687}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Simonton, D.K. | year=1999 | title=Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity | publisher=Oxford University Press}} |

||

| + | * {{cite journal | author=Smith, S.M. & Blakenship, S.E. | year=1991 | journal=American Journal of Psychology | title=Incubation and the persistence of fixation in problem solving | volume=104 | pages=61–87}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Sternberg, R.J. | coauthors=Lubart, T.I. | chapter=The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms | editor=ed. Sternberg, R.J. | title=Handbook of Creativity | year=1999 | publisher=Cambridge University Press | authorlink=Robert Sternberg}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Tatarkiewicz, Władysław | authorlink=Władysław Tatarkiewicz | title=A History of Six Ideas: an Essay in Aesthetics | location=Translated from the Polish by [[Christopher Kasparek]], The Hague | publisher=Martinus Nijhoff | year=1980}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Taylor, C.W. | chapter=Various approaches to and definitions of creativity | editor=ed. Sternberg, R.J. | title=The nature of creativity: Contemporary psychological perspectives | year=1988 | publisher=Cambridge University Press}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Torrance, E.P. | title=Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking | year=1974 | publisher=Personnel Press | authorlink=Ellis Paul Torrance}} |

||

| + | * [[Marie-Louise von Franz|von Franz, Marie-Louise]], ''Psyche and Matter'' (Shambhala, 1992) ISBN 0-87773-902-1 |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Wallas, G. | title=Art of Thought | year=1926 | authorlink=Graham Wallas}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Weisberg, R.W. | year=1993 | title=Creativity: Beyond the myth of genius | publisher=Freeman}} |

||

| + | * {{cite book | author=Ward, T. | year=2003 | chapter=Creativity | editor=ed. Nagel, L. | title=Encyclopaedia of Cognition | location=New York | publisher=Macmillan}} |

||

| + | *Andersen, B., Korbo, L., & Pakkenberg, B. (1992). A quantitative study of the human cerebellum with unbiased stereological techniques. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 326, 549-560. |

||

| − | ==External links== |

||

| + | *Imamizu, H., Kuroda, T., Miyauchi, S., Yoshioka, T., & Kawato, M. (2003). Modular organization of internal models of tools in the cerebellum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 100, (9), 5461-5466. |

||

| − | *[http://www.thebridge.org.uk/ Explore, Express and Discuss "Inherent Creative Ability"] |

||

| + | *Jung-Beeman, M., Bowden, E., Haberman, J., Frymiare, J., Arambel-Liu, S., Greenblatt, R., Reber, P., & Kounios, J. (2004). Neural activity when people solve verbal problems with insight. PLOS Biology, 2, 500-510. |

||

| − | *[http://www.ahapuzzles.com/ Aha! Puzzles - Original creative puzzles by Lloyd King] |

||

| + | *King, L. A., McKee Walker, L., & Broyles, S. J. (1996). Creativity and the five-factor model: Journal of Research in Personality Vol 30(2) Jun 1996, 189-203. |

||

| − | *[http://www.mycoted.com/creativity/techniques/index.php Creativity Techniques ] |

||

| + | *Miller, E., & Cohen, J. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24, 167-202. |

||

| − | *[http://www.crinnology.com/ A wiki for Creativity Techniques ] |

||

| + | *Miyake, A., & Shah, P. (Eds.). (1999). Models of working memory: Mechanisms of active maintenance and executive control. New York: Cambridge University Press. |

||

| − | *[http://www.creax.net CREAX - a collection of creativity-oriented links] |

||

| + | *Schmahmann, J. (Ed.). (1997). The cerebellum and cognition. New York: Academic Press. |

||

| − | *[http://www.best100ideas.com Creative ideas for business and personal uses] |

||

| + | *Schmahmann, J. (2004). Disorders of the cerebellum: Ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 16, 367-378. |

||

| − | *[http://all-creativity.info/How_to_be_More_Creative_and_Enhance_Your_Creativity_Adam_Eason.html How to be More Creative and Enhance Your Creativity] |

||

| + | *Vandervert, L. (2003a). How working memory and cognitive modeling functions of the cerebellum contribute to discoveries in mathematics. New Ideas in Psychology, 21, 159-175. |

||

| − | *[http://www.thegodofcreativity.org Learning creativity through quotes, aphorisms, proverbs and cartoons by Paul Palnik.] |

||

| + | *Vandervert, L. (2003b). The neurophysiological basis of innovation. In L. V. Shavinina (Ed.) The international handbook on innovation (pp. 17-30). Oxford, England: Elsevier Science. |

||

| − | *[http://www.worshipinfo.com/materials/creativity.htm Creativity in the Bible] |

||

| + | *Vandervert, L., Schimpf, P., & Liu, H. (2007). How working memory and the cerebellum collaborate to produce creativity and innovation [Special Issue]. Creativity Research Journal, 19(1), 1-19. |

||

| − | *[http://frontpage.et.byu.edu/mfg201/Lecturenotes/lecture2.htm Creativity - Lecture notes from a university course] |

||

| − | *[http://www.creativeeducationfoundation.com/index.shtml The Creative Education Foundation], which characterises itself as a non-profit organization of [[leader]]s in the field of creativity theory and practice. |

||

| − | * [http://www.helpguide.org/aging/creative_play_fun_games.htm Playing Together for Fun: Creative Play and Lifelong Games] |

||

| − | *[http://www.swemorph.com/pdf/gma.pdf General Morphological Analysis: A General Method for Non-Quantified Modelling] From the [http://www.swemorph.com Swedish Morphological Society] |

||

| − | * [http://www.m1creativity.com/map2003/maphome2.htm Mental Athletics Programme] - An interactive, practical and fun way to explore business creativity |

||

| − | * [http://www.m1creativity.com/tube/tube.htm Creativity & Innovation Tube line] - a novel visual representation of the creativity & innovation process |

||

| − | * [http://www.globaldharma.org Global Dharma Center] - Website of a non-profit organisation working on the field of Creativity, Business and Spiritual Values. Provides free downloads in the form of research publications, training modules, articles etc on the above mentioned themes. |

||

| − | * http://www.zideas.com/reading_room1.htm/ |

||

| − | * [http://www.swemorph.com/zwicky.html About Fritz Zwicky] From the [http://www.swemorph.com Swedish Morphological Society] |

||

| − | *[http://www.mindmedia.com/links/creativity.html Creativity on the Mind Media Guide] |

||

| − | *[http;//www.Creatology-triz.com][Iran Research Center for Creatology,Innovation and TRIZ][International Center for Science of Creatology(Founder:Sayed Mahdi Golestan Hashemi] |

||

| + | ==References== |

||

| − | |||

| + | *Amabile, Teresa M; Barsade, Sigal G; Mueller, Jennifer S; Staw, Barry M. Affect and creativity at work. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2005. v. 50, p. 367-403. |

||

| + | * Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1996). ''Creativity : Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention''. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-092820-4 |

||

| + | *Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218-226. |

||

| + | *Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., & Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1122-1131. |

||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== |

||

| + | {{wikiquote}} |

||

'''Essays:''' |

'''Essays:''' |

||

| + | * [http://www.anti-knowledge.com/book/00_Title.htm Knowledge Machine] - Online book with chapters on creativity including 1) creativity fallacies, 2) the sum of creative method, and 3) intelligence, genius, creativity, and knowledge creation |

||

| − | * [http://members.aol.com/mindwebart3/marcel.htm ''The Creative Act'' by [[Marcel Duchamp]]. (1957)] |

||

| + | * [http://web.archive.org/20000209000741/members.aol.com/mindwebart3/marcel.htm ''The Creative Act'' by [[Marcel Duchamp]]. (1957)] |

||

| + | * [http://cogprints.org/1569/ Metaphor and Mental Duality] |

||

| + | * [http://cogprints.org/1627/ Creativity: Method or Magic?] |

||

| + | |||

| + | '''Other articles:''' |

||

| + | * http://www.fekreno.org/englishLISTFEK.HTM |

||

| + | * http://about-creativity.com interviews with working artists about what works |

||

| + | |||

| + | '''Professional societies:''' |

||

| + | * http://www.AmCreativityAssoc.org/ American Creativity Association |

||

| + | [[Category:Aptitude]] |

||

| − | {{Wikibooks}} |

||

| + | [[Category:Creativity| ]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Cognition]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Educational psychology]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Personality traits]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Virtues]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Creativity]][[ Creatology ]] |

||

| + | <!-- |

||

| + | [[ar:إبداع]] |

||

[[da:Kreativitet]] |

[[da:Kreativitet]] |

||

[[de:Kreativität]] |

[[de:Kreativität]] |

||

| + | [[et:Loovus]] |

||

| + | [[es:Creatividad]] |

||

[[eo:Kreivo]] |

[[eo:Kreivo]] |

||

[[fr:Créativité]] |

[[fr:Créativité]] |

||

| + | [[it:Creatività]] |

||

| + | [[he:יצירתיות]] |

||

[[lt:Kūryba]] |

[[lt:Kūryba]] |

||

[[nl:Creativiteit]] |

[[nl:Creativiteit]] |

||

| + | [[ja:創造力]] |

||